Femoral nerve palsy secondary to iliopsoas haemorrhage in patients with haemophilia: results from biceps femoral transfer

Enrique Vergara-Amador, MD1, Marcela Piña-Quintero, MD2, Fernando Galván-Villamarín, MD3,

Camilo Abril-Aguilar, MD4

1. Profesor Asociado, Unidad de Ortopedia, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, DC, Colombia. e-mail: emvergaraa@unal.edu.co

2. Ortopedista y traumatóloga, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, DC, Colombia. e-mail: marcelapina@gmail.com

3. Ortopedista pediátrico, Hospital de la Misericordia, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, DC, Colombia.

e-mail: fergavil2001@yahoo.com

4. Residente de Ortopedia, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, DC, Colombia. e-mail: andcamabril@hotmail.com

Recibido para publicación febrero 19, 2009 Aceptado para publicación septiembre 30, 2009

SUMMARY

Hemophilia causes injuries of peripheral nerves secondary to compressions by hematoma. In general, these injuries recover spontaneously after the cause of the compression is solved. A case of a 16-year-old adolescent with injury of the left femoral nerve, causing loss of the extension of the knee is described herein. During the evolution there was no recovery. For this reason a tendinous transfer of the femoral biceps was practiced. This technique was described formerly for the correction of poliomyelitis. Excellent results were obtained with complete recovery of the extension and force 4+/5.

Keywords: Haemophilia; Femoral nerve; Iliopsoas; Haemorrhage.

RESUMEN

La hemofilia causa lesiones de nervio periférico secundarias a compresiones por hematoma. En general estas lesiones se recuperan espontáneamente después de resolverse la causa de la compresión. Se describe el caso de un adolescente de 16 años con lesión del nervio femoral izquierdo que ocasionó la pérdida de la extensión en la rodilla. Como durante la evolución no hubo recuperación, se hizo una transferencia tendinosa del bíceps femoral, técnica descrita antiguamente para correcciones en poliomielitis. Hubo un excelente resultado con recuperación completa de la extensión y fuerza 4+/5.

Palabras clave: Hemofilia; Nervio femoral; Hemorragia; Psoas ilíaco.

After hemarthrosis, muscular bleeding is the second source of spontaneous musculo-skeletal hemorrhages for hemophiliac patients. It involves 30% of the total number of bleeding episodes and causes a local inflammatory response with fibrosis and functional abnormality.

One of the most frequently affected muscles is the iliopsoas, the main flexor of the thigh, which originates in the retroperitoneum in the bodies of the lumbar vertebrae and crosses the pelvis before its insertion in the lesser trochanter of the femur. It can be compromised by lesions that are traumatic in origin, abnormalities in coagulation, and in surgery of the spinal column1 with a frequency of 11%-21% in hemophiliac patients2,3.

Its clinical appearance is characterized by lower abdominal or inguinal pain associated with edema, reduction in articular mobility and hip flexion3. The diagnosis is confirmed through ultrasonography, computed axial tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging, which is also useful during follow up4.

The objective of the treatment is to control bleeding and pain through the replacement of the deficient factor until it has reached 50% to 70% of the normal level. This is associated with rest until it has been progressively and spontaneously corrected. After pain and bleeding are controlled, rehabilitation is initiated5. On few occasions, the progressive increase in the hematoma may cause neurovascular compromise and even require open or percutaneous surgical drainage.

In 37% of the cases, depending on the size of the hematoma, the femoral nerve is compromised3. This complication causes a deficiency in knee extension with hypoesthesia on the anterior-internal face of the muscle and the internal face of the leg. This neuropathy usually corrects itself spontaneously during the first six months after the hematoma is corrected6. Surgical treatment of irreversible lesions of the femoral nerve in patients with traumatic or neurological pathology has been based on tendinous transference of the hamstring tendon, mainly of the femoral biceps, to the patella or quadriceps with good functional results7,8. After extensive search in Medline-Pubmed, Cochrane, and Imbiomed, no reports were found in the literature of cases of persistent femoral neuropathy secondary to a hematoma of the iliopsoas muscle due to hemophilia treated by tendinous transference of the biceps.

CLINICAL CASE

This 16-year-old patient had forty days of progressive left inguinal pain, with local heat and edema, limited mobility of the hip without antecedents of trauma. He was initially treated with analgesics and physiotherapy without improvement. There were antecedents of severe hemophilia A without inhibitor titers diagnosed at 7 months of age with replacement of factor VIII after bleeding episodes. He had repeated hemarthrosis in the right knee that caused arthropathy and flexion contracture. Two brothers died during their first weeks of life from severe hemophilia A.

Upon arrival, there was a slightly painful, deep, palpable mass in the left inguinal region with flexion retraction of the hip at 45º. An initial clinical diagnosis of a hematoma in the inguinal region was made. He was hospitalized with analgesics and replacement of factor VIII. Laboratory findings reported: hemogram with leucocytes, 1700; neutrophils, 67%; lymphocytes, 27%; hemoglobin, 8.9; hematocrit, 30%; and platelets, 452,000. The radiography of the pelvis showed an increase in the soft tissue in the region proximal to the left muscle and the CAT scan of the pelvis confirmed a muscular hematoma of the left iliacus with anterior and medial displacement of the psoas muscle. The ultrasonography of the hip showed a solid, heterogenous, 20 x 6 x 4.5 cm mass that was well-defined in the iliopsoas muscle.

Treatment was continued with analgesics, rest, factor replacement and observation. Later, cutaneous traction was applied for progressive extension of the hip and physical therapy was started. Pain and left ilioinguinal tumefaction persisted with deficiency in mobility and signs such as hypoesthesia, a reduction of the left patellar reflex, and absence of knee extension indicating that the left femoral nerve was compromised. Electromyography and nerve conduction tests revealed severe partial lesion of the left femoral nerve with signs of denervation. The follow up ultrasonography of the hip showed reduction of the hematoma. Mononeuropathy due to hematoma compression of the left femoral nerve was diagnosed. The process of rehabilitation was continued. The follow up electromyography two months later showed persistence of severe axonal lesion of the left femoral nerve with no evidence of recovery.

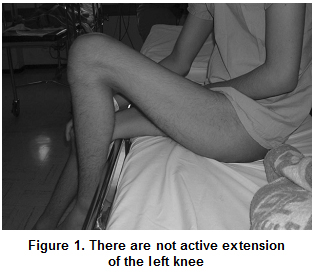

The patient continued to show no clinical improvement. New electromyography and nerve conduction tests done after five months showed a complete lesion of the left femoral nerve with total blockage of its conductivity, signs of denervation, and no voluntary muscle contraction. He presented normal reflex H of the left tibial nerve, which contributed to reject lesions proximal to the tibial nerve including sacral plexus and left L5 and S1 roots. Clinically, the patient continued to have hypoesthesia in the area of the affected nerve and no active extension of the left knee (Figure 1).

Eight months after the initial lesion, surgical treatment was performed to transfer the femoral biceps to the anterior rectus of the quadriceps femoris muscle using a lateral approach (Figure 2). Then, the knee was immobilized in extension with a full-length cast. No complications appeared. The cast was removed after 8 weeks and rehabilitation was started with progressive improvement in the flexion and extension of the knee.

After 18 months of surgery there was evidence of a complete active extension of the knee with strength of 4+/5 and flexion of 90º (Figure 3a). There were no complications. The follow up electromyographic findings showed a lack of recovery of the femoral nerve.

DISCUSSION

In most instances, a lesion to the femoral nerve secondary to a hematoma of the iliopsoas muscle in hemophilia resolves spontaneously with rest. However, there are some cases in which the severity of the hematoma causes an irreversible lesion3,5.

The functional deficiency generated by the paralysis of the quadriceps secondary to a lesion of the femoral nerve produces important abnormalities in the gait. That is a good reason to look for a surgical alternative to improve the extensor function of the knee. The tendinous transference of the biceps femoris for patients with poliomyelitis sequelae has been described and has had good results7,8. Other muscular transferences that utilize the deep fascia of the thigh, the sartorius, or the semitendinosus are described. Nevertheless, the reports did not show results as good as those found with the techniques based on the biceps femoris.

Transfer of the biceps femoris should be done by a lateral approach with careful dissection until the biceps tendon can be identified while protectively safeguarding the external popliteal sciatic nerve. It is detached distally and dissected proximally and, proceeding under the anterior rectus tendon, it is transferred to the upper surface of the patella and anchored with a non-absorbable suture.

In this patient, the suture was done with a maximum tension of 20 degrees of flexion on the knee and this was immobilized in extension postoperatively with a cast for 8 weeks. It is important to remember that surgery on patients with hemophilia requires supervision by both pediatrician and hematologist, as well as an adequate protection through pre- and post-surgical replacement of the deficient factor to prevent post-operative bleeding and, thus, improve the process of early rehabilitation.

This case illustrates and reminds us that there are techniques of muscular transference that are not commonly used at present, described for poliomyelitis, that can help us to obtain functional recovery of irreversible lesions of the femoral nerve in patients with hemophilia.

REFERENCIAS

1. Gertzbein SD, Evans DC. Femoral nerve neuropathy complicating iliopsoas haemorrage in patients without haemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg 1972; 54B: 149-51.

2. Balkan C, Kavakli K, Karapinar D. Iliopsoas haemorrhage in patients with haemophilia: results from one centre. Haemophilia 2005; 11: 463-7.

3. Fernández-Palazzi F, Hernández SR, De Bosch NB, De Sáez AR. Hematomas within the iliopsoas muscles in hemophilic patients: the Latin American experience. Clin Orthop. 1996; 328: 19-24.

4. Hermann G, Gilbert MS, Abdelwaha IF. Hemophilia: evaluation of musculoskeletal involvement with CT, sonography, and MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158: 119-23.

5. Goodfellow J, Fearn CB, Matthews JM. Iliacus haematoma. A common complication of haemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1967; 49B: 748-56.

6. Dingeman RD, Mutz SB. Hemorragic neuropathy of the sciatic, femoral and obturator nerves. Clin Orthop 1977; 127: 133-6.

7. Crego CH, Fischer FJ. Transplantation of the biceps femoris for the relief of quadriceps femoris paralysis in residual poliomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1931; 13: 515.

8. Schwartzmann JR, Crego CHJr. Hamstring-tendon transplantation for the relief of quadriceps femoris paralysis in residual poliomyelitis: a follow-up study of 134 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1948; 30A: 541-9.