Quality of life in persons living with HIV–AIDS in three healthcare institutions of Cali, Colombia

Claudia Patricia Valencia, MSc1, Gladys Eugenia Canaval, PhD1, Diana Marín2, Carmen J. Portillo, PhD3

1. Professor, Research

Group on Health Promotion ( PROMESA), School of Nursing, Universidad

del Valle. Cali, Colombia. Member of the International Nursing and HIV

-AIDS Research Network.

e-mail: claudia.p.valencia@correounivalle.edu.co glacanav@univalle.edu.co

2. Statistician, Hospital Epidemiology, Hospital Universitario del Valle, Cali, Colombia. e-mail: dmarin@hotmail.com

3. Professor School of

Nursing, University of California, Co-Director International Nursing

and HIV -AIDS Research Network. e-mail: cportillo@nursing.ucsf.edu

Received for publication November 4, 2008 Accepted for publication March 18, 2010

SUMMARY

Antecedents: The

Human Immunodeficiency Virus is currently considered a chronic disease;

hence, quality of life is an important goal for those suffering the

disease or living with someone afflicted by the virus.

Objectives:

We sought to measure the quality of life in individuals living with

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome virus and establish its relationship

with socio-demographic and clinical variables.

Methods:

This is a cross-sectional, descriptive study with a sample of 137

HIV-infected individuals attending three healthcare institutions in the

city of Cali, Colombia. Quality of life was measured via the

HIV/AIDS-Targeted Quality of Life (HAT-QoL) instrument. The descriptive

analyses included mean and standard deviation calculations. To

determine the candidate variables, we used the student t test and the

Pearson correlation. The response variable in the multiple linear

regression was the score for quality of life.

Results:

Some 27% of the sample were women and 3% were transgender; the mean age

of the sample was 35 + 10.2 years; 88% had some type of health

insurance; 27% had been diagnosed with AIDS, and 64% were taking

antiretroviral medications at the time of the study. Quality of life

was measured through a standard scale with scores from 0 to 100.

Participants’ global quality of life mean was 59 + 17.8. The

quality-of-life dimensions with the highest scores were sexual

function, satisfaction with the healthcare provider, and satisfaction

with life. The highest quality-of-life scores were obtained by

participants who received antiretroviral therapy, had health insurance,

lower symptoms of depression, low frequency and intensity of symptoms,

and no prior reports of sexual abuse. Eight variables explained 53% of

the variability of the global quality of life.

Conclusions: Those receiving antiretroviral therapy and who report fewer symptoms best perceived their quality of life.

Implications for

practice: Healthcare providers, especially nursing professional face a

challenge in caring to alleviate symptoms and contribute to improving

the quality of life of their patients.

Keywords: Quality of life; Symptoms,; HIV; AIDS; Health; Care; Nursing.

Calidad de vida en personas con VIH-SIDA en tres instituciones de salud de Cali, Colombia

RESUMEN

Antecedente:

Hoy en día se considera el VIH como una enfermedad

crónica; por tanto,la calidad de vida es una meta importante de

alcanzar en las personas que viven y conviven con el virus.

Objetivos:

Medir la calidad de vida en personas que viven con el virus del sida y

establecer la relación con variables socio-demográficas y

clínicas.

Métodos:

Estudio transversal, descriptivo, con muestra no probabilística

de 137 personas con VIH que asistieron a tres instituciones de salud de

Cali, Colombia. La calidad de vida se midió con el instrumento

Hiv/Aids-Targeted Quality of Life (HAT-QoL). El análisis

descriptivo incluyó los cálculos de promedio y

desviación estándar. Para determinar las variables

candidatas se utilizaron la prueba t de Student y la correlación

de Pearson. La variable respuesta en la regresión lineal

múltiple fue el puntaje de calidad de vida.

Resultados:

De los encuestados 27% eran mujeres y 3% transgéneros; la edad

promedio fue 35 + 10.2 años; 88% tenían algún tipo

de seguro de salud; 27% con diagnóstico de Sida y 64% con

tratamiento antirretroviral en el momento del estudio. La calidad de

vida se midió con una escala estandarizada de 0 a 100; el

promedio de calidad de vida global fue de 59 + 17.8; las dimensiones de

calidad de vida que mayor puntaje obtuvieron fueron la función

sexual, la satisfacción con el proveedor de cuidados de salud y

la satisfacción con la vida. Los puntajes más altos en

calidad de vida los obtuvieron personas que recibieron tratamiento

antirretroviral, con acceso a algún seguro de salud, menor

sintomatología depresiva, baja frecuencia e intensidad de

síntomas y sin antecedentes de abuso sexual. Ocho variables

explicaron 53% de la variabilidad de la calidad de vida.

Conclusión:

Las personas que reciben tratamiento antirretroviral y que informan

menos síntomas son quienes mejor perciben su calidad de vida.

Implicaciones para la práctica. Los proveedores de salud

especialmente los profesionales de enfermería tienen un reto en

el cuidado para aliviar los síntomas y hacer un aporte a la

calidad de vida de los pacientes.

Palabras clave: Calidad de vida; Síntomas; VIH; Sida; Salud; Cuidado; Enfermería.

Herein, we introduce

the results obtained on quality of life from the third study titled

«Symptoms and self-care in people with HIV-AIDS»1-3

conducted in different nodes by the International Nursing and HIV-AIDS

Research Network, led by the University of California. This article

presents the results from the node in the city of Cali, Colombia.

The

concept of health and its relationship with quality of life has been

suggested by several authors from different approaches. Health has been

traditionally seen as an aspect opposed to disease, even though the

World Health Organization (WHO) redefined it over five decades ago as a

state of complete wellbeing, still today health and its promotion are

not emphasized by the programs of healthcare providers for individuals

with some diagnosis of chronic disease like that related to Human

Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals (PLWHA); this has led

healthcare providers and researchers to make measurements of the health

and wellbeing of individuals in very limited manner4.

Quality

of life is a goal of health systems and of public health policies;

quality of life is currently a measurement that indicates the lack of

or presence of wellbeing, it is a measurement that is used as a

positive indicator regarding individuals’ relationship with

health and it is used to measure the effects or its relationship with

disease4.

Quality

of life is a term implying happiness and satisfaction with life and

adequate functioning. It is a very broad term and conceptually quite

complex; furthermore, it is a multidimensional concept. Health is one

of the dimensions of quality of life, but it is not the only one; other

dimensions have to do with financial aspects, interrelationships,

sexuality, work, as well as cultural and spiritual aspects5.

The path of the HIV disease is characterized by episodes of acute exacerbation and long periods of relative health6.

If the HIV disease advances, the result is diminished quality of life.

Although quality of life is a multidimensional construction that does

not accomplish universal agreement, some agreements have been reached

regarding its relationship with7. The WHO defines it as the

individual perception of the position towards life within the context

of culture and value systems in which individuals live in relation to

their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns4.

Quality

of life is a particularly important measurement to determine the

effects of the HIV-AIDS disease. Bearing in mind that this is a chronic

disease and that the life expectancy of Human Immunodeficiency

Virus-Infected Individuals (PLWHA) is increasing because of

developments in treatments and the dramatic change in mortality

measurements, we do not expect deaths of individuals infected by this

virus if treatment is appropiate8. In spite of this, it has

been reported that antiretroviral therapy (ARV) causes symptoms that

affect, to a greater or lesser degree, PLWHA and impacts on their

quality of life9.

Objectives

1. To measure the quality of life in a sample of individuals living with the AIDS virus in the city of Cali, Colombia.

2. To identify the

relationship between global quality of life and its specific dimensions

to some clinical and socio-demographic variables.

METHODOLOGY

Cross-section,

observational, and descriptive study conducted between 2005 and 2006,

with a non random sample of 137 patients with HIV-AIDS attending

ambulatory services at three healthcare institutions in Cali. The

patients were approached on the day of their medical or nursing

consultation and those who accepted voluntary participation and had the

availability of time to answer the survey were included. Among the

inclusion criteria defined were: subjects over 18 years of age, with or

without antiretroviral therapy, and with or without AIDS diagnosis at

the time of the study.

The

instruments used in measuring the variables included in the study have

been broadly validated in different research projects and are of free

distribution and use; these are: Demographic data questionnaire (age,

gender, social security), Depression Scale from the Center for

Epidemiological Studies [Escala de Depresión del Centro de

Estudios Epidemiológicos (CES-D)], Revised Signs and Symptoms

Checklist in people with HIV (SSC-HIVrev), HIV/AIDS-Targeted Quality of

Life (HAT-QoL) instrument.

Depression Scale from the Center for Epidemiological Studies (CES-D). Measures

symptoms of depression; it has 20 statements, responses range from 0

(never or rarely) to 3 (almost always or always). The total sum may

range from 0 to 60 and a score of 16 or more indicates the need for a

diagnostic evaluation for major depression. An estimated Alpha

coefficient of 0.90 was obtained in a sample of 727 AIDS patients9.

Revised Signs and Symptoms Checklist in people with HIV (SSC-HIVrev).

This is a 3-part checklist. Part I consists of 45 points and 11

factors, with confidence estimates ranging from 0.76 to 0.91; Part II

consists of 19 symptoms related to HIV/AIDS, which are not grouped into

factors but which can be of interest from the clinical perspective; and

Part III has eight points related to gynecological symptoms. These

eight points were subjected to principal components factor analysis

with varimax rotation (N = 118 HIV positive women), which yielded a

solution of a factor that explained 71.8% of the variability; the

confidence measurement of 0.9410.

HIV/AIDS-Targeted Quality of Life (HAT-QoL). This is a specific instrument to measure quality of life in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals (PLWHA)11.

It has nine dimensions: «General Function» (which is a

combination of the physical and social functions); «satisfaction

with life»; «concerns about health»; «financial

concerns»; «concerns about medications»;

«concerns about their HIV condition»; «concerns about

disclosing their diagnosis»; «confidence in the healthcare

provider»; «sexual function». The total final

evaluation was transformed into a linear scale from 0 to 100, where 0

is the worst possible score and 100 is the best possible score.

The Project was

approved by the Human Ethics Review Institutional Committee at

Universidad del Valle. Prior to applying the data gathering instrument,

the informed consent form was read explaining the objectives of the

study and the conditions of free and voluntary participation. All the

participants signed the informed consent form.

Data analysis. For

the descriptive analysis of quantitative variables like quality of life

and frequency of symptoms, the mean and standard deviation were

calculated and percentages were calculated in categorical variables.

The bivariate analysis to determine differences in quality-of-life

scores included the verification of the normality assumption with the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test, the Student t test, and calculation of

the Pearson correlation. The 95% confidence interval (CI95%) was

calculated for measurement differences. The linear regression was used

to determine the factors related with quality-of-life scores. The

purpose with the construction of this model was more explicative than

predictive, which is why no variable selection method was used. The

global adjustment of the model was verified with the one-way ANOVA; the

pertinence of each variable was verified via the statistical t test;

fitting of the model was verified with the adjusted determination

coefficient and the assumptions of residues were verified through the

following manner:

1. Normality and zero means: with the K-S test, the Q-Q plot, and the residue histogram

2. Homoscedasticity: via residue plot versus predicted values.

3. No self-correlation: with the Durbin-Watson statistical package.

4. Multicollinearity: with the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)

The results were analyzed via the SPSS version 13 statistical package.

RESULTS

The results were

handled per instructions by the authors. The population studied

consisted of 96 (71%) men, 37 (27%) women, and 4 (3%) transgender; 88%

of the subjects reported having some type of health insurance, most

(57.3%) belonged to the subsidized healthcare regime of the Health and

Social Security System. Twenty-seven percent had been diagnosed with

AIDS and 64% were receiving antiretroviral therapy at the time of the

study. Regarding age, the mean was 35.3 + 10.2 years with a range from

20-73 years, 9% were above 50 years of age. The day of the interview,

the participants reported an average of 17+11 symptoms, the data of the

characteristics of the sample are published in depth in another article

by Valencia et al.1

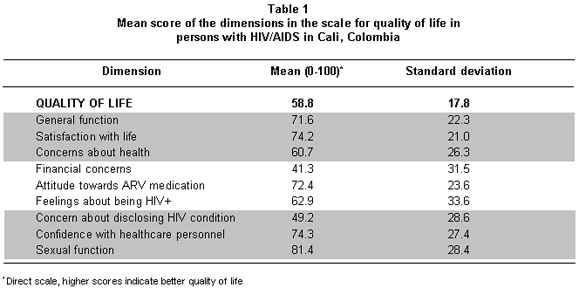

Quality of life. The average global quality-of-life score in the sample of patients was 59+17.8 points in a standardized scale from 0-100. Table 1

shows the score for each of the nine quality-of-life dimensions. Note

that the lowest scores in the dimensions correspond to financial

concerns (41.3) and to the difficulty of disclosing their HIV condition

(49.2). The dimensions revealing the best scores are sexual function

(81.4), satisfaction with life (74.2), and satisfaction with attention

received from healthcare personnel (74.3).

The

bivariate analysis per healthcare regime (type of insurance) revealed

that individuals in the contributive regime had a better global score

on the quality-of-life scale compared to the global score of

individuals with subsidized regime (average: 66.21 vs. 53.8,

respectively; p=0.00). These statistically significant differences are

also observed in the scores for the following dimensions:

«general function», «concerns about health»,

«financial concerns», and «concerns about their HIV

condition» (Table 2). Regarding sex,

statistically significant differences were only found in the dimension

on concerns about health, which is lowest for the female group (52.8

vs. 63.5; p=0.032).

Upon

analyzing quality of life according to age, statistically significant

difference was only found in the dimension for «confidence with

the attention offered by the healthcare provider»; this being the

highest quality-of-life score for those over 50 years of age (93 vs.

72.4; p=0.0120).

No

statistically significant differences were observed between individuals

with or without children under their care. Regarding the relationship

between quality of life and treatment or not with antiretroviral

medication therapy (ARV), it was found that quality of life is

generally better for those taking the medications than for those who

were not taking them (66 vs. 46; p=0.00). Analyzing the relationship

between ARVT and the different dimensions of the scale, significant

differences were noted in the dimensions dealing with «financial

concerns and concerns about disclosing their HIV+ condition»

(47.6 vs. 30; p=0.001 and 70.1 vs. 49.7; p=0.000, respectively). To

explore the relationship between symptoms and quality of life, we

measured the relationship with the average frequency of symptoms, the

intensity of the symptoms, and the symptoms of depression. The score

for quality of life was lower among those with symptoms of depression

– both in the global score (63.9 vs. 51.97; p=0.000) and in the

dimensions of general function (p=0.000), concerns about health

(p=0.02), concerns about their HIV condition, concerns about ARV

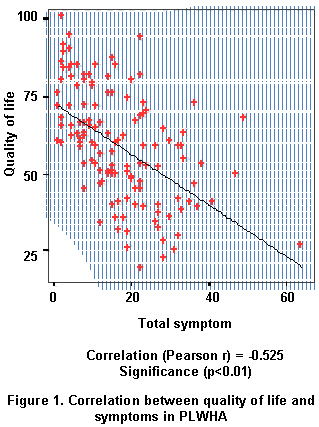

medications (p=0.008), and sexual function (p: 0.005). The Pearson

correlation between quality of life and frequency of symptoms revealed

that as symptoms increase the quality of life is impaired (r: -0.525

p<0.05) (Figure 1).

Multivariate analysis. To

determine factors related to quality of life and its nine dimensions,

we used a multiple linear regression for global quality of life and

nine models separated for each of the dimensions. Eight of the nine

variables included in the model for quality of life explain 53% of the

variability in quality-of-life scores; however, it was found that only

the frequency of symptoms and the use of ARV therapy are significant to

explain quality of life (p<0.01). The negative coefficient (-.340,

t=-4.962, p=0.000), for the first variable, indicates that the number

of symptoms increase in an individual with HIV, global quality of life

diminishes; the positive coefficient (.437, t=6.335, p=0.000), for the

second variable, indicates that individuals who received ARV therapy

have better quality of life than those who did not receive it. The

model fulfills all the statistical suppositions; no multicollinearity

problems were found, and the variance was homoscedastic and the

distribution of residues was normal.

Table 3

shows the regression models for the dimensions with the greatest number

of independent variables. It is noted that the amount of symptoms

(frequency of symptoms) negatively affects the following dimensions:

general function, satisfaction with life, concerns about health, and

concerns about medications. For the dimension on concern about being

HIV+, the bivariate or multivariate analyses did not reveal variables

to explain that dimension.

Increased

frequency of symptoms, the presence of depression, sexual abuse, and

being over 50 years of age negatively affect the dimension of

«satisfaction with life». These variables explain 31.8% of

the variance for this dimension. In the dimension on concern about ARV

medications, it is noted that taking them improves the quality of life

in said dimension by 26%, and along with the physical abuse and

frequency of symptoms variables help to explain 45% of the variability

in that dimension.

Individuals

over 50 years of age (p=0.021) who are in the contributive healthcare

regime (p=0.003), have greater scores in the dimension of

«confidence with the healthcare provider»; both variables

-along with the constant- explain 21.1% of the global variability of

that dimension. In other dimensions, it is noted that quality of life

is affected by symptoms of depression and by being or not being

affiliated to healthcare insurance; the dimension on «financial

concerns» is negatively affected in individuals with

subsidized-type healthcare regime; the sexual function dimension is

most affected in individuals suffering from depression (p=0.016).

DISCUSSION

The results in this

study agree with reports from other studies; diverse factors like the

symptoms perceived by PLWHA have been associated to lower

quality-of-life scores12; likewise, some social characteristics have been associated with a low quality-of-life index13.

In contrast, factors like middle or high economic level in terms of

income and not having children under their care have been associated to

better quality of life14. In general terms, it is observed

that the global variability explained by the variables in each of the

dimensions is quite high compared to results obtained by Phaladze et

al.7

In this

study, the patients with the highest quality-of-life scores had better

access to healthcare services. Those affiliated to a contributive

healthcare regime had better-quality services; presenting fewer

financial concerns, fewer symptoms of depression, received

antiretroviral therapy, and experienced lower frequencies and

intensities of symptoms; they also evidenced fewer antecedents of

sexual or physical abuse. These findings are similar to those reported

by Phaladze et al.7 who found a close correlation between

intensity of symptoms and low quality of life, at the expense of

patients’ functional capacity impairment. Our results, like

others, show that high frequency and intensity of symptoms have

negative effects on quality of life15,16 and on satisfaction for life; additionally, increased states of depression impairs quality of life.

Several studies13,17,18

have identified an inversely proportional relationship between quality

of life and poverty, as suggested by the results in this study. Hence,

the socioeconomic conditions determine greater vulnerability in

acquiring the infection, as well as in living with a better quality of

life. This phenomenon denotes the continuity of the chain of social

factors characterizing this disease, turning it into a vicious circle:

lower income is consequential of lack of work and, thus, less access to

healthcare services. This situation also diminishes possibilities for

access to antiretroviral therapy and to integral healthcare services,

which contributes to worsening of psychological and physical conditions

of individuals affected by AIDS and their families. The results confirm

statements made by other authors in that the quality of life of

individuals with HIV/AIDS is a complex constellation of disease,

poverty, stigma, discrimination, and lack of treatment.

This

study did not reveal a statistically significant association between

quality of life and gender. A significant relationship was only

identified in one of the dimensions in the quality-of-life scale,

concerns about health and gender, showing that women have a lower

quality of life with respect to concerns generated by their health

condition. Relationships with the adherence variable are not presented

in this article.

CONCLUSION

Frequency of signs and

symptoms and taking ARV medications were the variables most associated

to quality of life in inverse relationship for the first, i.e., a

greater number of signs and symptoms indicate lower quality of life;

and in direct association, for the latter, meaning better quality of

life among those receiving medications. These aspects correlate with

the natural history of the disease, which has shown that the benefits

of antiretroviral therapy in terms of the prognosis are greater than

the adverse effects noted specifically at the beginning of therapy.

These findings agree with those reported by other authors like Wu12.

Improving the immune system and diminishing viremia translates to

lesser symptoms, lowered options of developing opportunistic

infections, and greater chances of reinsertion into the social

environment and the labor market. These factors are undoubtedly

reflected in the different dimensions measuring quality of life. Figure 2

presents the scheme of the variables related to global quality of life

and with their dimensions in individuals living with the AIDS virus.

Implications for practice and research. The

HIV/AIDS disease is a public health issue, given the dimensions of its

propagation. Given that it is a chronic disease, this study suggests

several challenges and questions to address from different disciplines,

especially from the field of nursing: How to improve in society and in

nursing care the quality of life of individuals living with the AIDS

virus?

·

Health professionals and society in general can adopt positive

attitudes and educate their patients to live better with HIV/AIDS.

· Healthcare

services must adequately and continuously provide medications to their

users so they can keep their illness under control.

· Nursing can teach and support strategies to reduce functional limitations such as nutrition and exercise.

· Nursing can

provide support and education for self-care and family care that

contribute to diminishing the frequency and intensity of the symptoms.

· Maintaining a

good quality of life requires healthcare with a holistic and integral

focus, given the different dimensions that define it.

Limitations.

This study was conducted on a non random sample of patients among those

attending health ambulatory medical and nursing control services in

three healthcare institutions in the city of Cali. The results can be

extrapolated to patients with similar characteristics, which is why we

recommend further studies with random samples of patients.

Conflict of interest. None of the authors has conflicts of interest related to this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded

by the Colombian Institute for the Development of Science and

Technology (COLCIENCIAS) through contract Nº 11060416327 and by

the School of Nursing at Universidad del Valle in Cali, Colombia.

REFERENCES

1. Valencia CP, Canaval GE,

Rizo V, Correa D, Marín D. Signos y síntomas en personas

que viven con el virus del SIDA. Colomb Med. 2007; 38: 365-74.

2. Nicholas PK, Kemppainen

JK, Canaval GE, Corless IB, Sefcik EF, Nokes KM, et al. Symptom

management and self-care for peripheral neuropathy in HIV/AIDS. AIDS

Care. 2007; 19: 179-89.

3. Nicholas P, Voss J,

Corless I, Lindgren T, Wantland D, Kemppainen J, Canaval GE, et al.

Unhealthy behaviors for self-management of HIV-related peripheral

neuropathy. AIDS Care. 2007; 19: 1266-73.

4. Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC). Measuring healthy days. Population

assessment of health- related quality of life. Atlanta: CDC; 2000.

5. Ferrans CE. Quality of life: Conceptual issues. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1990; 6: 248-54.

6. Nokes MK, Coleman C,

Hamilton MJ, Corless IB, Selcik E, Kirsey K, et al. Health-related

quality of life in persons younger and older than 50, who are living

with HIV/AIDS. Res Aging. 2000; 22: 290-310.

7. Phaladze NA, Human S,

Dlamini SB, Hulela EB, Hadebe IM, Sukati NA, et al. Quality of life and

the concept of living well with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. J Nurs

Schol. 2005; 37: 120-6.

8. Palella FJJr, Delaney KM,

Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining

morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human

immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators.

New Engl J Med. 1998; 338: 853-60.

9. Holzemer WL, Henry SB,

Nokes KM, Corless IG, Brown M, Powell Cope GM, et al. Validation of the

sign & symptom check list for persons with HIV disease

(SSCHIV). J Adv Nurs. 1999; 3: 1041 49.

10. Holzemer WL, Hudson A,

Kirskey K, Hamilton MJ, Bakken S. The revised sign and symptom check

list for HIV (SSC-HIV rev). J Assoc Nurs AIDS Care. 2001, 12: 60 -70.

11. Holmes WC, Shea JA. A new

HIV/AIDS-targeted quality of life (HAT- QoL) instrument: development,

reliability, and validity. Med Care. 1998; 36: 138-54.

12. Wu AW, Dave NB,

Diener-West M, Sorensen S, Huang, IC, Revicki DA. Measuring validity of

self-reported symptoms among people with HIV. AIDS Care. 2004; 16:

876-81.

13. Lorenz KA, Shapiro MF,

Asch SM, Bozzette SA, Hays RD. Associations of symptoms and

health-related quality of life: findings from a national study of

persons with HIV infection. Ann Int Med. 2001; 134: 854-60.

14. Préau M, Leport C,

Salmon-Ceron D, Carrieri P, Portier H, Chene G, et al. Health-related

quality of life and patient-provider relationships in HIV-infected

patients during the first three years after starting PI-containing

antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Care. 2004; 16: 649-61.

15. Bing EG, Hays RD,

Jacobson LP, Chen B, Gange SJ, Kass NE, et al. Health-related quality

of life among people with HIV disease: Results from the multicenter

AIDS cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2000; 9: 55-63.

16. Call SA, Klapow JC,

Stewart KE, Westfall AO, Mallinger AP, DeMAsi RA, et al. Health-related

quality of life and virologic outcomes in an HIV clinic. Qual Life Res.

2000; 9: 977-85.

17. Hays RD, Cunningham WE,

Sherbourne, CD, Wilson IB, Wu AW, Cleary PD, et al. Health-related

quality of life in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection

in the United States: results from the HIV cost and services

utilization study. Am J Med. 2000; 108: 714-22.

18. Sousa KH, Holzemer WL,

Henry SB, Slaugther R. Dimensions of health-related quality of life in

persons living with HIV disease. J Adv Nurs. 1999; 29: 178-87.

|