Latissimus dorsi transposition for sequelae of obstetric palsy

Enrique Vergara-Amador*

*Associate

Professor, Hand surgeon and Pediatric orthopedist, Department of

Orthopedics, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, DC,

Colombia. Ancient resident, Institut Francais de la Main, Paris,

France.

e-mail: emvergaraa@unal.edu.co

Received for publication July 23, 2009 Accepted for publication May 7, 2010

SUMMARY

Background: In

obstetric palsy, limitation in the external abduction and rotation of

the shoulder is the most frequent sequelae. Glenohumeral deformity is

the result of muscular imbalance between the external and internal

rotators. Releasing the contracted muscles and transferring the

latissimus dorsi are the most common surgeries in this case.

Patients and methods: We

operated on 24 children between 4 and 8 years of age with obstetric

palsy sequelae to elevate the subscapularis muscle off the anterior

surface of the scapula posteriorly and transfer the latissimus dorsi.

The patients received a minimum of 2 years of follow up. They were

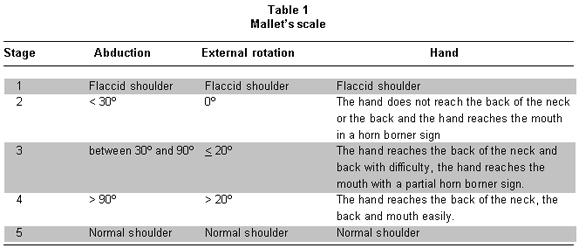

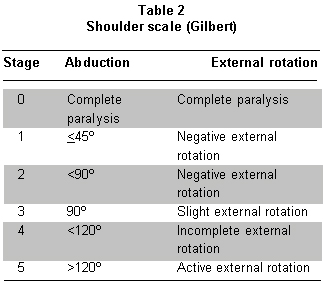

evaluated based on Mallet’s and Gilbert’s classifications.

Results: All of the

patients recovered within the above mentioned classifications. Out of

22 children evaluated via Mallet’s classification, all improved

from 3 to 4 on that scale. With respect to Gilbert’s

classification, 16 children improved one degree and 8 improved 2

degrees. All of the patients’ parents were satisfied with the

results.

Discussion: The benefit

from releasing contracted muscles and muscle transfer to improve

shoulder abduction in the sequelae of obstetric palsy has been amply

reported in the literature. The results we had from elevating the

subscapularis muscle off the anterior surface of the scapula and

transferring the latissimus dorsi were good. Children who were

difficult to classify based on the described scale were taken note of

and some sub-classifications for Gilbert’s descriptions were

proposed. Patients must be selected carefully. To transfer the

latissimus dorsi, it is necessary to have good passive mobility in

abduction, a minimum of 20º of external rotation and no joint

deformities. When negative external rotation is found, the

subscapularis muscle should be released. When there is glenohumeral

joint deformity in older children, other methods are recommended, such

as rotational humeral osteotomy.

Keywords: Obstetric palsy; Transfers muscular shoulder; Latissimus dorsi; Subscapular.

Transferencia del músculo dorsal ancho en secuelas obstétricas del plexo braquial

RESUMEN

Introducción:

Las limitaciones en la abducción y la rotación

externa del hombro son las secuelas más frecuentes en la

parálisis obstétrica. Se encuentra deformidad de la

articulación glenohumeral como resultado del desequilibrio que

existe entre los músculos rotadores externos e internos. Dentro

de las cirugías más usadas para corregir las deformidades

del hombro están las liberaciones musculares y la

transposición del músculo dorsal ancho.

Materiales y métodos: El

autor operó 24 niños entre los 4 y 8 años de

edad, con secuelas de parálisis braquial

obstétrica, a quienes se les practicó liberación

del subescapular por vía posterior y transferencia del

músculo dorsal ancho. Se evaluaron según la escala de

Mallet y la de Gilbert, con un seguimiento mínimo de dos

años.

Resultados: Todos los

niños se recuperaron según las escalas mencionadas. En 22

evaluados según Mallet, todos mejoraron del nivel 3 al 4.

Según la clasificación de Gilbert, 16 niños

mejoraron un grado y 8 niños mejoraron dos grados. Todos los

padres estuvieron satisfechos con los resultados.

Discusión:

Existen muchos informes en la literatura médica sobre los

beneficios de liberar los músculos contracturados y de las

transferencias musculares en el hombro en las secuelas de

parálisis braquial obstétrica. Se obtuvieron buenos

resultados en todos los niños. Algunos casos fueron

difíciles de clasificar en las escalas usadas, para lo cual se

propone una sub-clasificación. Se requiere tener una buena

movilidad pasiva, que no haya deformidad articular en el hombro y

mínimo 20º de rotación externa, para realizar la

transferencia muscular del dorsal ancho. Cuando no se encuentra la

rotación externa, se debe hacer la liberación del

subescapular. Si hay deformidad de la articulación glenohumeral,

no se recomiendan las transferencias musculares y entonces se recurre a

osteotomías.

Palabras clave: Parálisis braquial obstétrica; Transferencia muscular; Dorsal ancho.

In obstetric brachial plexus injuries, most patients recover

spontaneously without surgery. The nerve roots frequently compromised

by typical Erb’s palsy are C5 and C6, where an absence of

abduction and external rotation of the shoulder, flexion of the elbow

and supination of the forearm are found. When the C7 nerve root is

affected, a deficit in the extension of the hand is gene-rally found.

Many of the total injuries at the beginning recovery of the lower

roots and remain a definitely lesion of the upper plexus. Non-recovery

of the bicep flexion against gravity before 3 to 4 months of age or of

the deltoids has been an indication that plexus exploration is necessary1-3.

This indication has been extended to 6-9 months by different authors

who have argued that nerve reconstruction procedures are useful up to

the first year of age4,5. Good functioning is expected for

children who recover anti-gravity biceps strength before the age of 6

months. In the case of children whose biceps recover before the age of

6 weeks, it is possible to achieve total recovery6.

Limitation in abduction and external rotation caused by weakness in the

deltoid muscles and the external rotators of the shoulder are the most

frequent secondary deformities. Contracture in adduction and internal

rotation could appear early due to the lack of opposition to the muscle

forces generated by the subscapularis, pectoralis major, teres major

and latissimus dorsi.

This difficulty in performing external rotation will produce posterior

subluxation of the humeral head in the long term, causing it and the

glenoid to become deformed. This will in turn bring about limitation in

mobility and pain in the long run7,8. Early reconstruction,

along with the release of the contracted tendons and tendinous

transfers, will improve passive and active mobility and retard

deformities in the glenohumeral joint9,10.

Releasing the compromised structures includes elevation of the

subscapularis muscle. This can be done on the tendinous part of the

muscle but it is not generally recommended because of the risk of

residual instability. It can also be done through the posterior

approach by releasing the muscle on the anterior surface of the scapula5,11-13 and releasing the teres major and the pectoral major.

The transfer of the latissimus dorsi muscle is done to improve external

rotation and the abduction at the same time. In 1934, L’Episcopo14 described the transfer of the latissimus dorsi and teres major to the lateral humerus to improve external rotation. Hoffer10

described the transfer of the latissimus dorsi by taking it posterior

and superior in a rotator cuff to allow greater external rotation and

abduction with a functional deltoid. When a good latissimus dorsi does

not exist, transfers of the trapezium or of the scapula elevator may be

considered12,15,16.

The purpose of this article is to describe the results in a case series

with in the transfer of the latissimus dorsi with the elevation of the

subscapularis muscle off the anterior surface of the scapula in

children with obstetric palsy sequelae.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

There were 24 patients with obstetrical brachial plexus sequelae who

had operations performed by the same surgeon (EVA), between 1997 and

2006, to transfer the latissimus dorsi, which, in the cases of 11

children, was associated with elevation of the subscapularis muscle.

There was a minimum follow up of 2 years. Movement of the shoulder was

limited in all cases, especially in abduction and external rotation,

which made it difficult to carry out some ordinary daily activities

like getting dressed, combing the hair, and lifting objects to the face

or mouth. Six patients had an operation on the plexus before they were

one year of age and 18 had not received any surgical treatment.

A transfer of the latissimus dorsi to the infraspinous and supraspinous

tendon was done on all of the patients. Releasing the subscapularis

muscle was done at the same time on 11 patients except for one who had

been operated on at 3 years of age to elevate just the subscapularis

muscle. The criteria for releasing the subscapularis muscle was

external passive rotation of less than 20º. All the patients had

normal morphology in the X-rays. When there was a poor image on the X-

ray, a CT scan was taken. The average age at the time of surgery was

5.1 years of age (ranging from 4 to 8 years of age). The minimum age

for surgery was 4; patients were evaluated before and after the

operation based on Mallet’s scale and the scale for the shoulder

described by Gilbert (Tables 1, 2).

Surgical technique.

The patient is placed in lateral decubitus position under general

anesthesia. An approximately 5 cm axial incision is made on the lateral

border of the scapula when a release of the scapula is being planned.

When only a transfer is planned, the incision is made in the posterior

axillary fold; it is dissected subcutaneously and the interval of the

latissimus dorsi with the teres major is located on the external border

of the scapula. If the latissimus dorsi is of poor quality, the teres

major will be added to the transfer. Because the teres major is

smaller with a lesser excursion than the latissimus dorsi, the teres

major is released from the latissimus dorsi and sutured to the same

muscle more proximally, thus, integrating the two muscles to the

transfer. The dissection towards the humerus is performed with extreme

care. It is not necessary to see the radial nerve. This last part can

be done with blunt dissection up to the insertion of the latissimus

dorsi into the humerus. The muscle is released and lifted while being

careful not to exert tension on the vascular-nervous pedicle. With the

latissimus dorsi lifted, we reach the lateral border of the scapula and

the subscapularis muscle is lifted subperiosteally, starting on the

lateral and inferior border and continuing towards the medial and

superior border with a periosteal elevator. It is important to release

the medial corners because, if not, the subscapularis muscle cannot

slide well. After that, the shoulder should rotate 30º externally.

If it is not possible to achieve good external rotation at the moment,

consider releasing the anterior capsule of the shoulder and of the

coracohumeral ligament (CHL) without cutting the subscapularis muscle

tendon.

The latissimus dorsi tendon goes under the deltoids and it is sutured

to the infraspinous on the lateral superior part. A fast anchor was not

used in any case. If abduction improvement is rendered, the latissimus

dorsi is sutured to the supraspinatus tendon with the arm at maximum

external rotation and an abduction of 90 to 120º. The wound is

closed in two layers with absorbable suture. The arm is immobilized in

a position of minimal abduction of 90º degrees and with external

rotation in the Statue of Liberty position for 5 weeks. When

rehabilitation is started, immobilization is continued at night for

three more weeks.

RESULTS

Overall, we obtained good results; there were no hematomas,

neurological or vascular injuries, nor infection. Of 22 patients scored

on Mallet’s functional scale, all were at 3 points before surgery

and improved to 4 points. Based on Gilbert’s scale, 13 patients

were at 3 before surgery and improved to 4. Seven patients were at 2

and improved to 4. One patient was at an intermediate classification

between 2 and 3 and improved to 4. One patient went from 3 to 5, and

two patients went from 4 to 5. In other words, all of the patients

improved in the two scales (Figures 1, 2; Table 3). The parents of the patients were satisfied with the functional results (Figures 3, 4).

DISCUSSION

External rotation and abduction of the shoulder with progressive

contracture in internal rotation and adduction are the most important

sequelae for the shoulder in obstetric paralysis. The muscular

imbalance between the weak external rotator (infraspinous) and the

strong internal rotators (teres major, latissimus dorsi, pectoral

major, and subscapularis) is the main factor for deformity in internal

rotation and adduction of the shoulder.

The subscapularis is the largest of the four rotator cuff muscles. Einarsson et al.17,

demonstrated the abnormal mechanical properties of the subscapularis

muscle in individuals with obstetric brachial plexus palsy when they

analyzed the passive mechanical characteristics of biopsies from the

subscapularis muscle obtained through open surgery.

Secondary deformities such as the elongation of the coracoids,

flattening or deformation of the humeral head with subluxation or

posterior dislocation and flattening or retroversion of the glenoid may

be found7,8.

Hoeksma et al.7, reported a 56% prevalence of contractures

greater than 10% and a 33% prevalence of osseous deformity in a series

of 53 patients treated without surgery. Waters et al.9, say

that the natural history of obstetrical brachial paralysis with

muscular weakness is glenohumeral deformity because of muscular

imbalance. Using computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) to evaluate the gleno scapular angle (retroversion) on a series

of 42 patients, the healthy side showed -5.5 on the average and the

affected side, -25.7 with 62% of the patients presenting posterior

subluxation and increased deformity with age.

Bahm et al.18, noted that although the muscular imbalance

might explain most of the progressing deformities of the glenohumeral

joint, it was necessary to be aware of the rare cases of connatal

traumatic subluxations of the humeral head, which can cause a rapid

contracture requiring immediate surgery.

The anterior release of the subscapularis muscle has been used

extensively but has the drawback of causing anterior instability in the

shoulder. Carlioz and Brahimi11 improved the external

rotation of the shoulder by releasing the subscapularis muscle off the

anterior surface of the scapula through a posterior approach. This is

indicated when the patient still has a congruent glenohumeral joint13,19.

If the external rotator muscles are weak, transfer of the latissimus

dorsi should be done immediately, as well. This transfer will improve

active abduction of the shoulder given that it stabilizes the rotator

cuff and makes the deltoids more effective13,16.

Pagnotta et al.13, evaluated 203 patients who had undergone

operations on their shoulders followed by long-term follow up. This

showed that individuals benefiting most from the surgery were children

who had C5 and C6 paralysis and those who scored 2 and 3 on the Gilbert

scale. According to the authors, six years after the surgery some

patients presented loss of abduction but kept external rotation. It is

possible that the cause of this is functional exclusion on the part of

the child and lack of rehabilitation.

All of the children in this report improved in abduction and external

rotation. Our follow up is relatively short and loss of abduction has

not been observed. All of the children improved on the functional

scales. The 22 who were evaluated based on Mallet’s scale

improved one degree. Eight patients improved two degrees and 16

patients improved one degree based on Gilbert’s scale. Two

children could not be correctly classified on Mallet’s scale

prior to surgery. They had more than 90º of abduction but a

deficit of external rotation of 0º and -20º.

We noticed patients who were not easily classified. There were children

who were found between Mallet’s classifications of 3 and 4. There

were patients whose degrees of abduction were greater than 90º,

but whose external rotations were less than 20º or negative,

making it impossible to classify them. Gilbert’s classification

gives us a closer approach to reality than Mallet’s, although

there are some patients whose recovery of abduction and external

rotation are dissociated. For example, case 16 presented abduction

greater than 120º, but an external rotation of 0º.

Currently, patients who are classified into stages 3, 4, and 5 on

Gilbert‘s scale are being evaluated and sub-classified. The

breakdown we used for this sub-classification is the following:

. 3A: abduction of 90º and external rotation of 0º or negative

. 3B: abduction of 90º and slight or positive external rotation

. 4A: abduction of less than 120º and external rotation of 0º or negative

. 4B: abduction of less than 120º and positive or incomplete external rotation

. 5A: abduction greater than 120º and external rotation less than 20º

. 5B: abduction greater than 120º and external rotation greater than 20º

The patients have to be carefully selected. Good passive mobility in

abduction, a minimum external rotation of 20º and no joint

deformities are required for the transfer of the latissimus dorsi. When

an external rotation of 0º or negative is found, releasing the

subscapularis muscle is considered. At the same time, we evaluated

whether or not it was necessary to release the major pectoral muscle.

Sometimes, though not in this series, it is necessary to release the

anterior capsule of the glenohumeral joint through an anterior approach

or the coracohumeral ligament.

When there is posterior subluxation or glenohumeral joint

deformity in older children, other methods are recommended such as

rotational osteotomy of the proximal humerus20.

No benefits in any form have been received or will be

received from any commercial party related directly or indirectly to

the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Gilbert A, Tassin JL. Surgical repair of the brachial plexus in obstetric paralysis. Chirurgie. 1984; 110: 70-5.

2. Waters PM.

Comparison of the natural history, the outcome of microsurgical repair

and the outcome of operative reconstruction in brachial plexus birth

palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999; 81-A: 649-59.

3. Birch R, Ahad N,

Kono H, Smith S. Repair of obstetric brachial plexus palsy: results in

100 children. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2005; 87-B: 1089-95.

4. Clarke HM, Curtis

C. Examination and prognosis. In: Gilbert A (ed.). Brachial plexus

injuries. London: Martin Dunitz in association with the Federation of

European Societies for Surgery of the Hand; 2001. p. 159-72.

5. Haerle M, Gilbert A. Management of complete obstetric brachial plexus lesions. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004; 24: 194-200.

6. Waters PM. Update on management of pediatric brachial plexus palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005; 14: 233-44.

7. Hoeksma AF, Ter

Steeg AM, Dijkstra P, Nelissen RG, Beelen A, Jong BA. Shoulder

contracture and osseous deformity in obstetrical brachial plexus

injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003; 85-A: 316-22.

8. Birch, R. Medial

rotation contracture, posterior dislocation of the shoulder. In:

Gilbert A (ed.). Brachial plexus injuries. London: Martin Dunitz in

association with the Federation of European Societies for Surgery of

the Hand; 2001. p. 249-59.

9. Waters PM, Bae DS.

Effect of tendon transfers and extraarticular soft-tissue balancing on

glenohumeral development in brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint

Surg. 2005; 87-A: 320-5.

10. Hoffer M,

Wickenden R, Roper B. Brachial plexus birth palsies. Results of tendon

transfers to the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg. 1978; 60-A: 691-5.

11. Carlioz H, Brahimi

L. La place de la désinsertion interne du sous-scapulaire dans

la traitement de la paralysie obstétricale du membre

supérieur chez l’enfant. Ann Chir Infantile. 1971; 12:

159-67.

12. Raimondi PL, Muse

A, Saporiti E. Palliative surgery: shoulder paralysis. In: Gilbert A

(ed.). Brachial plexus injuries. London: Martin Dunitz in association

with the Federation of European Societies for Surgery of the Hand;

2001. p. 225-38.

13. Pagnotta A, Haerle

M, Gilbert A. Long-term results on abduction and external rotation of

the shoulder after latissimus dorsi transfer for sequelae of obstetric

palsy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004; 426: 199-205.

14. Strecker WB,

McAllister JW, Manske PR, SchoeneckerPL, Dailey LA.

Sever-L’Episcopo transfers in obstetrical palsy: a retrospective

review of twenty cases. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990; 10: 442-4.

15. Chen L, Gu YD, Hu

SN. Applying transfer of trapezius and/or latissimus dorsi with teres

major for reconstruction of abduction and external rotation of the

shoulder in obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. J Reconstr Microsurg.

2002; 18: 275-80.

16. Van Kooten EO,

Fortuin S, Winters HA, Ritt MJ, Van der Sluijs HA. Results of

latissimus dorsi transfer in obstetrical brachial plexus injury. Tech

Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2008; 12: 195-9.

17. Einarsson F,

Hultgren T, Ljung BO, Runesson E, Fridén J. Subescapularis

muscle mechanics in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J

Hand Surg Eur. 2008; 33: 507-12.

18. Bahm J, Wein B,

Alhares G, Dogan C, Radermacher K, Schuind F. Assessment and treatment

of glenohumeral joint deformities in children suffering from upper

obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Pediatr Orthop (Br). 2007; 16:

243-51.

19. Gilbert A. Long-term evaluation of brachial plexus surgery in obstetrical palsy. Hand Clin. 1995; 11: 583-95.

20. Kirkos JM,

Papadopoulos IA. Late treatment of brachial plexus palsy secondary to

birth injuries: rotational osteotomy of the proximal part of the

humerus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1998; 80-A: 1477-83.

|