Self-rated health: Importance of use in elderly adults

José Mauricio Ocampo, MD*

* Assistant Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia.

e-mail: jmocampo2000@yahoo.com.ar

Received for publication February 19, 2010 Accepted for publication May 15, 2010

SUMMARY

Introduction: The

concept of self-rated health (SRH) was conceived during the first half

of the twentieth century. Since then, numerous studies have documented

the validity of its measurement and it has been widely accepted as a

reliable measurement of overall health. SRH is considered a subjective

measurement integrating the biological, mental, social, and functional

aspects of an individual.

Objective: To review the literature to determine theoretical determinants, related outcomes, and utility of SRH in elderly adults (EAs).

Methods:

The databases reviewed were Medline, SciELO, EMBASE, Science Direct,

Proquest, and Ovid, along with information available in websites from

international health agencies.

Results:

SRH is considered a sensitive measurement of overall health in EAs. It

is influenced by physical function, the presence of disease, the

existence of disabilities, functional limitations, and by the rate of

aging. Many studies suggest it may be modified by demographics, as well

as by social and mental factors. Thus, the perception of health is the

result of multiple and complex interactions of variables determining it

at any given time. SRH is based on systems theory and the

bio-psychosocial health model. It has proven to be a significant

independent predictor for development of morbidity, mortality, and

disability in basic physical and instrumental daily life activities

among elderly adults.

Conclusion:

In addition to reflecting the overall health status of EAs, SRH can

provide information to aid health personnel and decision makers in the

development and implementation of health promotion and disease

prevention programs, as well as the adequacy and planning of different

levels of care for this population.

Keywords: Self-rated health; Elderly adults; Daily life activities; Aging; Bio-psychosocial model.

Auto-percepción de salud: importancia de su uso en adultos mayores

RESUMEN

Introducción:

El concepto de auto-percepción de salud (APES) fue introducido a

mitad del siglo XX. Desde entonces, numerosos estudios han documentado

la validez de su medición y ha sido ampliamente aceptado como

una medida confiable del estado de salud general. La APES se considera

una medición subjetiva que integra factores biológicos,

mentales, sociales y funcionales del individuo.

Objetivo:

Realizar una revisión de la literatura para determinar

fundamentos teóricos, factores determinantes, desenlaces

relacionados y utilidad de la APES en adultos mayores (AM).

Metodología:

Se utilizaron las bases de datos Medline, SciELO, EMBASE, Science

Direct, Proquest, Ovid, así como la información

disponible en sitios web de organismos sanitarios internacionales.

Resultados:

La APES se considera una medida sensible del estado general de salud en

los AM. Está influida por la función física, la

presencia de enfermedades, la existencia de discapacidades, de

limitaciones funcionales y por el tipo de envejecimiento. Muchas

investigaciones sugieren que la pueden modificar variables

demográficas, sociales y mentales. De esta manera, la APES es la

resultante de múltiples y complejas interacciones de variables

que la determinan en un momento dado. La APES se fundamenta en la

teoría de sistemas y en el modelo bio-psicosocial de salud. Se

ha demostrado que se comporta como un predictor independiente y

significativo para desarrollar morbilidad, mortalidad y discapacidad,

tanto en las actividades básicas cotidianas como en los aspectos

físico e instrumental en adultos mayores.

Conclusión:

La APES además de reflejar el estado de salud global del AM,

puede brindar información que ayude al personal de salud y a

tomadores de decisiones en el desarrollo e implementación de

programas de promoción de la salud y prevención de la

enfermedad, así como en la adecuación y

planificación de diferentes niveles asistenciales para este

grupo poblacional.

Palabras clave: Autopercepción de salud; Adulto mayor; Actividades básicas cotidianas; Envejecimiento;

Modelo bio-psicosocial.

Population aging is

probably the most important demographic phenomenon in the world during

the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century1.

The population of elderly adults (EA), defined as individuals 60 years

of age and older present 2.4% growth rates, compared to 1.7% for the

total population. It is expected that this growth rate increases by

3.1% as of 2010. In absolute numbers, this shows that the EA group will

increase from 616-million in 2000 to 1.209-billion in 2025, implying

that this population group will double in numbers every 25 years1.

The

aging process can lead to gradual deterioration of mental and physical

health conditions, reduction in expected years of active and healthy

life, and complete or partial cease in participation in the labor market2.

Likewise, alterations in the health status -characteristic of advanced

age- are more chronic than acute and more progressive than regressive.

This makes it necessary to know the state of health of this population

so it can be intervened from the vantage point of health promotion and

disease prevention, as well as for the adequacy and planning of the

care offered and for the development of health programs.

To

accomplish this, it is necessary to start by being clear on the concept

of health status as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in

1945, thus: «A complete state of physical, mental, and social

wellbeing and not merely the lack of disease or disability»3.

This definition, in schematic manner, circumscribes health within a

quadrant in which the extremes correspond to the physical, mental,

social, and spiritual dimensions. Additionally, it is stressed that the

concept of health should bear in mind the human being as a total and

integral being. This focus permits visualizing the four dimensions

mentioned in independent and integrated manner in individuals, in whom

these dimensions function as a complete entity and in relation to the

world around them.

Consequently,

this holistic view makes the assessment of the state of health to

become a complex activity, particularly in EAs because during the aging

process a series of internal and external modifications take place, as

well as changes in the functions of the individual’s organs and

systems. This becomes evident when the person is exposed to stressful

situations that induce changes in the state of health, as a product of

lower functional reserve and lower capacity for response and

adaptation, a phenomenon known as homeoestenosis, which can lead to

greater probability of organic failure and illness4.

With

respect to assessment of state of health in EAs, it is fundamental to

bear in mind that it is integral and such then go beyond the

traditional clinical history. Therefore, this assessment must consider

the psychological, familial, social, economic, and functional dimensions5.

It is worth mentioning that this assessment, more than in other age

groups, implies subjectivity, because it depends on the interaction

among physiological conditions, functional abilities, psychological

wellbeing, and social support. For this reason, the evaluation of the

state of health should not bear in mind only the strictly medical

aspects, it should go beyond, being relevant for clinicians, decision

makers, and researchers working with this population group5.

WHAT IS SELF-RATED HEALTH STATUS AND WHAT ARE ITS ORIGINS?

In spite of the

generalized use of the term self-perception, there is no clear

definition of its meaning in scientific literature; there is also no

clarity of its theoretical concept. Self-perception can be defined as

the concept individuals have of themselves and based on such; they

process and organize the information of their context within a

structure that provides the basis of principles to act in the present

and in the future. Thus, individuals maintain and develop a basic

scheme of their own self-perception throughout their whole lives6.

Self-Rated

Health has been employed in a broad variety of scenarios with different

population groups and for a great number of objectives ranging from

screening for specific health conditions to studies designed to aid in

decision making for individuals in crisis situation, like depressive

states or the capacity to decide on changing domicile7. As

mentioned, in the previous paragraph the term SRH has been used to

refer to the response made by individuals when asked about their state

of health; hence, it can be applied to all self-reports of state of

health or of specific symptoms like pain or the sensation of dyspnea,

fatigue, or tiredness7.

In

other words, SRH is a way of evaluating the state of health in people,

which integrates information on the biological, mental, functional, and

spiritual dimensions of an individual’s health8.

Thereby, it is considered that SRH represents the perception

individuals have of the different dimensions of their state of health;

accordingly, SRH can be classified as a result and integral variable,

which permits inferring that it can encompass the different dimensions

of the human being9.

The SRH

concept has been included in different research projects since the

1950s and ever since then diverse studies have shown its usefulness in

documenting the state of health self-reported by EAs during a given

moment and also in predicting future health-related events8,9.

This shows the great interest in using SRH when conducting research

that assesses state of health; in fact, it is already part of health

surveys carried out with EAs.

WHAT ARE THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS OF SRH?

For the theoretical

understanding of SRH, a model made up of four dimensions is proposed.

Said dimensions are defined by their content, i.e., by the aspect each

seeks to evaluate. In turn, between dimension and dimension there are

multiple interactions. The type of self-perception we wish to assess

depends on the dimension predominating in such interaction and on its

characteristics, for example, if the approach tends to be more general

or specific and if it seeks to evaluate social aspects, health aspects,

or both7 (Graphic 1).

Hereinafter,

we present the different approaches of the evaluation according to the

dimensions and type of self-perception, based on the proposal by

Griffiths et al.7

·Health care approach. This

domain focuses on assessing specific health aspects and problems.

Self-perception can collaborate and, on occasion substitute the

assessment made by the health professional. For example, based on this

domain, research has been conducted to identify elderly adults with

mental disorder, hearing and vision loss, and problems with nutrition,

mobility, and function. This type of self-evaluation can help to

predict current needs and some future ones. When an approach to

self-perception is conducted through this domain, the

individual’s internal factors are exclusively considered.

· General health care approach.

This domain is used for evaluating a broad range of factors related to

health care. The objective here is to improve general health care and

mediate in the patient’s relationship with healthcare

professionals. Mental health status, functional capacity, social

contacts, and use of health services are among the aspects investigated

in this domain. This type of assessment permits determining the

individual’s current needs, and can sometimes aid in predicting

future needs, although it does not permit identifying the resources

available for the individual. When approaching self-perception through

this domain, internal and external factors of the individual are

considered.

· Social care and abilities for life approach.

This domain focuses on assessing everyday situations and aspects the

health professional does not frequently evaluate during consultation,

like the individual’s capacity to drive a vehicle and the

possibility of being involved in accidents. Aspects related to home

safety along with risks of falling are also assessed. This provides

greater elements for patient assessment and care. When approaching

self-perception through this domain, internal factors of the individual

are considered, as well as external factors like environment,

employment, and leisure time.

· Multidimensional approach. This

domain involves external factors like social aspects and internal

factors like the individual’s state of health and wellbeing. The

main objective of this domain lies in identifying necessities and

offering information that permits the individual to adequately satisfy

such. Because of the great number of factors this domain can encompass,

it is possible that it includes elements of self-assessment of social

care along with life skills and the impact of the state of health. The

distinction between the domain of general health care and the

multidimensional approach lies on the balance and weight given to

health problems and services. If the approach is multidimensional, a

global approximation is made of the aspects related to the

individual’s state of health, unlike general health care that

emphasizes health needs and services for the individual.

Different

research has shown that measuring personal health perception is a

useful global indicator of the population’s level of health,

given that it reflects social and biological elements10,11.

In effect, SRH is one of the mostly used types of self-perception to

determine the state of health in EAs from a subjective perspective,

because it shows multiple aspects of the individual’s state of

health that could turn out to be difficult to obtain via traditional

quantitative research methods. For example, objective measurements

often evaluate only one aspect, as with levels of glycated hemoglobin

that are used in determining the state of control of diabetes mellitus.

It could be said that the subjective and objective measurements are

complementary and necessary when learning of the individual’s

state of health. Consequently, SRH is considered a type of

self-perception employing elements from the multidimensional approach

according to WHO recommendations12.

For the theoretical explanation of SRH, we used the bio-psychosocial model suggested by Engel13,

which approaches health from a holistic view and which considers the

individual a being participating in the social, psychological, and

biological spheres; in contrast to the analytical, reductionist, and

specialized biomedical model, which additionally takes into account the

person as an object and ignores that person’s subjective

experience as a possibility of also being studied in scientific manner14.

On the

contrary, the bio-psychosocial model considers an illness not as the

lack of health or simply physical health but also any psychological or

social interaction that can affect and individual’s state of

illness/disability.

Understanding

the bio-psychosocial model requires an approach to the General Systems

Theory, whose main exponent was Ludwig von Bertalanffy15,

and stemming from this approach there can be integration between the

parts and the whole, where relationships are not unidirectional but

bidirectional and there is no cause and effect unicausal relationship,

but one of multifactorial effect. With this, an important change is

produced given that understanding the phenomena the simple thought

«first A then B» is not sufficient, but rather the capacity

of thinking of the complexity of the multiple interactions.

With

respect to the SRH model suggested, a set of independent variables is

shown that are grouped according to the state-of-health dimension to

which they belong in social, demographic, biological, mental, and

functional terms. From a subjective perspective, individuals will

self-report their state of health. This implies that people must

undergo complex reasoning involving multiple interactions of

independent variables for the self-report of the state of health.

This

interaction of multiple variables permits obtaining information on the

state of health of the elderly adult during different moments, i.e.,

the current state of health compared to that of other individuals of

similar age and the current state of health actual compared to that of

the previous year. Additionally, said interaction may offer prospective

elements that help to anticipate the development of any given event in

the future.

On this

matter, SRH behaves as an intermediate variable among the independent

variables that determine it and the different outcomes to which it has

been associated like death, hospitalization, and functional impairment

among others16 (Graphic 2).

WHY IS THERE INTEREST IN RESEARCHING SRH?

Many health

professionals treating elderly adults focus mainly on factors related

to physiological measurements (laboratory values), mental state

(presence of depression), life styles (smoking habit), or functional

state (Basic Daily Activities). However, studies have shown that the

perceptions offered by EA son their state of health and wellbeing can

be as important as the clinical variables to evaluate and predict the

evolution of the state of health over time9.

Unfortunately,

current clinical medicine practice has progressively stopped listening

to patients (their ailments), and has replaced this for observation or

measurements like diagnostic images or application of scales17.

This has caused medicine to go from being a discipline involved with

listening and feeling, to a discipline of seeing and doing; proof of

this is the increase in the algorithms and guides for clinical practice

in recent years. That could explain why the question on the perception

of the state of health is often ignored; in fact, the medical practice

prefers to inquire more about quantitative than qualitative aspects,

for example, on inquiring about sleep the question is how many hours

does the patient sleep per day, rather than how does the patient feel

with his/her sleeping habits18.

As has

been insisted upon in this article, different studies have shown that

assessing the personal perception of the state of health is useful

because it allows globally describing the population’s level of

health given that it reflects elements that are not merely biological,

but also psychological, social, and functional10,11. It has

also been employed to compare the state of health of EAs from different

countries, because it can be easily obtained and reflects multiple

aspects of the state of health that could be difficult to gather by

other methods19.

Analyzing

the factors related with SRH will permit identifying health needs and

evaluating programs and interventions aimed at EA population group.

Hence, it should be included in research for the following reasons9:

·

It is a global measurement of the state of health, psychological

wellbeing, and quality of life related to health, offering much more

information than other variables used in traditional research, for

example, the presence of chronic illness or total cholesterol values,

among others.

· It is easily

obtained through one single question: «Do you consider your

general health status: excellent, very good, good, regular, or

poor?» This shows that specialized personnel are not required to

assess a population’s general state of health.

· It is an

indicator significantly associated with the population’s state of

health and with mortality; consequently, it can be used approximately

to determine healthcare needs.

· It behaves as

a screening test because it helps to identify high-risk individuals in

prodromal stages for the development of adverse health events like

falls, and hospitalization among others.

· At the

individual level, it may predict mortality in the elderly; thereby,

useful in current or future behavioral models to determine, for

example, the use of retirement services or plans.

·It may be used to tailor health services and establish priorities in healthcare.

WHAT STUDIES HAVE BEEN CONDUCTED IN LATIN AMERICA ON SRH IN ELDERLY ADULTS?

In Colombia, not much research has been done on SRH in EA populations. One of these was done by Gómez et al.20

who carried out an observational analytical, cross-section study in the

city of Manizales, where SRH assessment was done and established a

correlation with the presence of co-morbidity and functional state. The

researchers found an important association among SRH, chronic disabling

disease, and functional capacity, measured via the Barthel scale, which

evaluates Basic Daily Activities in the physical aspect.

Recently, Parra et al.21

conducted a multilevel observational analytical, cross-section study to

determine the association between urban and environmental

characteristics in the city of Bogotá with SRH and quality of

life related to health. A positive association was found between

perception of neighborhood safety with good SRH and quality of life

related to health. Likewise, the availability of recreational spaces

like safe parks that promote social interaction and recreational

activities was associated to good SRH and quality of life in the mental

health domain. On the contrary, zones with high levels of noise were

associated to bad SRH and quality of life. The value of this research

lies in that it is the first study conducted in a highly urbanized city

in a country with low to medium economic income. Additionally, it

offers inputs to implement interventions aimed at improving the quality

of life and SRH of EAs living in cities with environmental and

socioeconomic characteristics that are similar in several Latin

American nations.

Hambleton et al.22

carried out an observational analytical, cross-section study, employing

information belonging to the population of Barbados in the «SABE

project», which is a multicenter survey conducted in seven urban

centers in Latin America and the Caribbean to evaluate the factors

impacting the health and wellbeing of EAs 60 years of age or more. The

study sought to determine the relative contribution of past events and

current experiences to the state of health of EAs for the purpose of

conducting opportune sanitary interventions for said population. It was

found that past experiences of socioeconomic aspects influenced SRH,

and over half of the influence exerted by past events was measured by

current experiences related to the socioeconomic situation, life style,

and the presence of illnesses. Therefore, when caring for the elderly,

consideration must be made for intervention of the risk factors related

to life style. The importance of this research lies on the relationship

established by the authors between social and clinical determinants

with SRH. Consequently, when implementing programs to reduce poverty

and increase Access to healthcare and education, long-term strategies

should be considered aimed at improving the health of the elderly of

the future.

Alves et al.23

employed information from a population in Sao Paulo, Brazil from the

«SABE project» to carry out an observational analytical

cross-section study. The purpose of that work was to determine, via

SRH, the relationship between demographic, social, and economic factors

along with the presence of chronic disease and functional capacity in

EAs 60 years of age and older. The study also sought to evaluate if

there were gender differences. It was found that presence of chronic

disease in relation to gender was the greatest association to determine

SRH, i.e., males presenting four or more chronic illnesses had 10.53

times greater opportunity for bad SRH; similarly, for females it was

8.31 times. Likewise for educational level, income, and functional

capacity were related to SRH. The novel aspect of this research is the

approach of SRH from the multidimensional perspective, and that it may

be useful for decision makers when implementing actions from the health

sector seeking to promote wellbeing and quality of life for the elderly.

Reyes et al.24 led

an observational analytical cross-section study, employing information

from the multicenter survey in the «SABE project». The aim

was to determine the relationship between religiosity and SRH. It was

found that most (90%) reported having some religious affiliation, and

within this group 80% considered religion important in their lives. The

EAs who considered religion very important in their lives had lesser

opportunity of reporting bad SRH when compared to those who considered

religion less important. This is one of the first studies carried out

in urban centers in Latin America and the Caribbean showing the

importance of religiosity in the state of health of elderly adults.

HOW IS SRH MEASURED?

In recent years,

surveys employed to assess state of health have used diverse questions

trying to integrate the different dimensions of the human being25.

These types of surveys take into account the self-report of health,

through a subjective, global, and integrating evaluation of the state

of health done by the individual. This includes the perception of small

physiological-type variations, negative or positive attitudes on life

and disposition for healthy conducts; these are related to clinical

morbidity, which is influenced by social, cultural and emotional aspects7.

To

assess SRH, a variety of schemes of structured questions has been

designed with their possible responses, among which there is the WHO

version employed in Europe and the United States version.

The

World Health Organization version, which is recommended and used in

Europe, takes a range of responses from very good to very poor. It is

characterized because it groups the responses into several categories,

of which two are positive (very good and good); one neutral (regular);

and two negative (poor and very poor)12.

The better known United States version is employed by Bjorner et al.26

who initially used the question: How do you rate your state of health?;

with four possible response options: excellent, good, regular, or poor.

Then, a fifth «very good» response option was added, along

with an additional question on the current general state of health

compared to that of the previous year: How would you rate your current

general state of health, compared to that of the previous year? which

is how it is known and applied currently in different research

projects. These last additions were included because of the study

conducted by Ware et al.27 who used the abbreviated SF-36 form.

Regarding

SF-36, this is the instrument developed for use in the Medical Outcomes

Study, from an extensive battery of questionnaires, whose final format

provides a profile of the state of health28. It includes 36

points grouped into 8 scales: physical functioning, physical

performance, body pain, emotional performance, mental health, vitality,

general health, and social functioning, plus an additional one: change

of health over time. These points assess positive and negative states

of mental and physical health. For each dimension, the points are

coded, aggregated, and transformed into an ordinal scale ranging from 0

(the worst state of health for that dimension) to 100 (the best state

of health), without generating a global index.

This

instrument has been used in over 40 countries in the International

Quality of Life Assessment Project. It is documented in more than 1,000

publications; its usefulness in estimating disease burden is described

in over 130 conditions and it is used worldwide because of its

briefness and comprehension. It is worth pointing out that in the

assessment made on Colombian adults a Spanish version was obtained

showing complete coincidence with the expected original, high

equivalency with the original values, and acceptable reproducibility,

concluding that the SF-36 is reliable in evaluating healthy quality of

life after it was linguistically adapted in Colombian adults29.

After

evaluating self-perception with a single question, SRH was used to

assess the perception individuals have of their own health in

comparison to other people of the same age; this provides greater

information than that offered by the concept of personal self-perception26. Table 1 shows the different questions that can be made when assessing state of health via SRH.

Also,

when comparing the two questions with their possible responses to

assess SRH, it has been found the WHO version discriminates the

negative categories better, unlike the version from the United States

that discriminates the positive categories better30.

However, both types of questions are highly correlated and have shown

similar associations with respect to demographic variables and health

conditions, as well as having a similar variation pattern when applied

in different countries31.

WHAT FACTORS DETERMINE SRH?

Self-rated Health may

be considered a global result of the measurement of multiple factors

determining it. In fact, it is influenced by demographic variables like

gender and age; social variables like social networks and family

functioning; biological variables like the presence of illnesses and

taking of medications; mental variables like suffering anxiety,

depression, dementia, or grief; and, lastly, functional variables like

presenting commitment in the physical and instrumental Daily Basic

Activities8.

The different factors determining SRH by group of variables are:

Demographic variables.

Regarding differences in SRH according to gender, diverse explanations

have been considered among which there are differences in the state of

health, wellbeing, and functionality and not in the greater or lesser

possibility of one or the other sex reporting a determined state of

health. This means the relationship between SRH and gender is mediated

by other factors like educational level, illnesses, depression, and

functional state. Here, it is worth mentioning that women report a

greater proportion of health problems and have greater diagnosis of

diseases like arterial hypertension, diabetes, musculoskeletal

disorders, and accidents, aside from presenting greater frequency of

affective disorders when compared to men. Given that women have higher

life expectancies and, therefore, a greater possibility of enduring

chronic disease that deteriorate their functionality, as those already

mentioned, this could explain why they evidence greater association

with the self-report of a bad SRH32.

Adding

to the aforementioned, women have a higher life expectancy than men.

This occurs at the expense of years lived with greater functional

deterioration, that is, the consequences of the disease affect the

internal and external perception of reality and translate to diminished

quality of life when diminishing the possibilities of being and doing,

which leads women to deteriorated perception of their own health and

limitation of activities, functions, and opportunities11. Thus, better SRH has been constantly found in men than in women and this is more notorious in the elderly.

Another

factor to bear in mind and that may explain a greater frequency of bad

SRH in women is their lower income, which diminishes as they get older,

and especially when they are very old10.

It has

also been postulated that with the passage of time in the elderly, SRH

tends to regular or poor, which can be explained by multiple factors,

including the loss of social roles, chronic disease and disability

among others20. In spite of this, individuals over 90 years of age may

paradoxically manifest good or excellent SRH, explained by different

factors among which include:

·

Heterogeneity of the aging process, which postulates that over the

years – in spite of higher risk of illness and deterioration of

the functional state, the elderly do not necessarily uniformly or

inevitably manifest bad SRH18.

· Elderly

adults take as reference groups other older individuals in whom

disabilities are the norm, which leads them t orate their health

positively; additionally, over time they start establishing adaptive

mechanisms to accept their own aging process, the presence of chronic

disease, and functional limitations33.

· Elderly

individuals are more optimistic regarding their health as they age,

because they have become accustomed and perceive illnesses and

functional impairment more optimistically than the younger individuals34.

· The survival

effect, i.e., those reaching 85 years of age constitute the group with

the highest optimism; while the most pessimist regarding their health

may have already perished35.

· Elderly

adults are a group that along the years has been exposed to multiple

stressing events and subject to natural selection so survivors tend to

be stronger and healthier34.

In

addition, with the passage of years SRH may have multiple paths, which

are determined by diverse bio-psychosocial factors, consequently

presenting great variability among individuals, which could also be

related with the type of aging shown by the EA. The types of aging that

have been described are successful, usual, or pathological36.

EAs with successful aging, unlike those with usual or pathological

aging, show high levels of physical, mental, and cognitive functioning,

as well as lack of or low probability of developing disease or

disability and an active commitment with life. EAs with usual aging

present non-pathological losses related with age and in pathological

aging there is evidence of disease with disability and its multiple

bio-psychosocial consequences36.

Regarding

the relationship between the type of aging and SRH, it has been

suggested that EAs with successful aging show good and stable SRH over

time; however, SRH begins to deteriorate after 80 years of age.

Nevertheless, paradoxically in some EAs 85 years of age and above SRH

can stabilize or improve, which is explained, as mentioned before,

because it is an optimistic group and because it is the result of

natural selection37. The elderly with usual aging report SRH

similar to EAs with successful aging although the SRH impairment

process begins earlier, around 70 years of age. Finally, EAs with

pathological aging have bad SRH as a base and their impairment

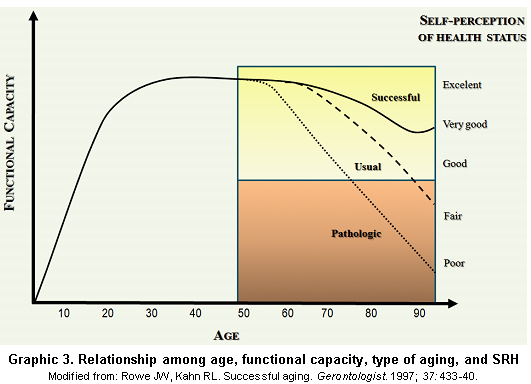

accelerates after 60 years of age34. Graphic 3 displays the relationship among age, functional capacity, type of aging, and SRH.

A

strong association has also been found between SRH and the

population’s socioeconomic level, given that the general state of

health is better in individuals with higher socioeconomic levels11.

However, exceptions are possible, particularly in certain populations

of elderly adults, because this is a very heterogeneous group and this

aspect may lead to important differences in the self-report of health19,37.

Educational

level is considered an important aspect determining better or worse

SRH, inasmuch as individuals tend to have a better perception of their

health when they have higher educational levels although they may have

a greater number of illnesses26. It is considered that

according to the educational level, the individual may have better

tools to face vital stressing moments and, consequently, may modulate

the result of SRH14.

Regarding

geographical location factors influencing SRH assessment, it has been

found that these differ from one country to another38. This

diversity of patterns may be due to the demographic and epidemiological

transition stage in which the populations are found39. For

example, in healthier populations the perception of better health may

depend to a greater extent on emotional health, on chronic disease, or

on functionality problems; while in populations with the worse health,

the general self-evaluation of health may be more affected by other

health problems like infectious disease38. Another possible

explanation for the differences found is that individuals with similar

levels of health perceive their state of health differently in

relationship with determined structural elements of the national

sanitary systems like quality of healthcare services or the importance

given to the illnesses they suffer19.

Likewise,

the use of healthcare services may be associated with the evaluation of

SRH; lowered use of sanitary services indicates better self-perception26.

Results of longitudinal studies have revealed that survival is more

related with subjective than with objective health and that healthcare

is one of the factors associated with satisfactory aging35.

Although

the subjectivity of SRH is acknowledged because it accounts for the

perception people have of their own health, this may have advantages in

cases where the population does not have generalized access to

healthcare services37. Much of the information about the use

of SRH in elderly adults and its relationship with other indicators

comes from developed nations8. The assessment of the

usefulness of this indicator in developing nations recently emerged

with studies carried out in some countries in Latin America and Asia38.

In

developed nations where there is greater contact between the population

and sanitary personnel, it is possible that the self-report of specific

disease like diabetes, arterial hypertension, or cancer is a better

indicator of the population’s health, because it is more

objective than the general evaluation of one’s own health40. However, even in developed nations, the self-report of specific disease may enclose large bias41.

In

general, it is suggested that during old age the decline of the ego is

intensified, deriving into a loss of identity, low self-esteem, and

decrease of social conducts2. In spite of the

aforementioned, having a stable relationship like a matrimony,

participation in community activities, and joining social groups may

help to maintain a sense of continuity including a more positive SRH,

even after retirement37.

Biological variables. Prior

awareness of an illness, particularly of chronic disease, suffered by

the person, may affect the judgment the individual has of SRH42.

Self-Rated

Health is specially influenced by somatic experience that generates the

illness. Somatic experiences are physical manifestations that may be

represented, for examples, by fatigue or a sensation of dyspnea, which

can make individuals interpret they are suffering a serious condition

and, consequently, modify their SRH. Knowledge of a potentially life

threatening, serious disease like coronary disease or cancer, may have

a greater impact on the individual, unlike knowing of a disease that

impairs functionality but is not life threatening like osteoarthritis

or hypertension, may lead to modifications of activities or behaviors

and especially a change in SRH. Hence, SRH is considered the product of

a process depending to a great extent on the information the individual

has of the subjective experience generated by the disease43.

The

presence of a disease may modify SRH, as can the clinical course; some

diseases, especially those involving organic systems, like congestive

heart failure, have periods of clinical stability but can also be

intercalated with periods of exacerbation. Thus, SRH represents a

complex judgment made by the individual at a given moment on the

severity of the current state of health, because the course of a

disease can be modified over time.

Also,

in spite these being personal perceptions EAs of their own health, some

studies have shown that the morbidity they perceive coincides by two

thirds with that diagnosed by health professionals32. In

studies, it has often been found an excellent or very good SRH in

individuals with good physical health; however, paradoxically, it has

also been noted that individuals with these same physical health

characteristics have regular or poor SRH. Later analyses have shown

that these individuals have symptoms of depression or dissatisfaction

with their lives18.

Mental variables. One

of the reasons why the self-concept, SRH, and their relationship with

age suppose a problem is the perception by EAs of feeling

psycholo-gically worse34. Indeed, depression is one of the

most frequent mental disorders for EAs. Prevalence for major depression

has been described at 1%-5% and a frequency of 8%-27% for significant

symptoms of depression in EAs living in the community44. The prevalence is greater in hospitalized elderly subjects, and in those living nursing homes45.

Frequently, depression emerges in EAs in atypical manner and does not

fulfill the clinical criteria for major depression. These incomplete

syndromes are denominated minor depression or subsyndromal depression

according to the diagnostic statistical manual for mental disorders

(DSM-IV) and have the same repercussions, in terms of morbidity and

mortality, as major depression46.

Depression

may involve cognitive processing, causing individuals to manifest lower

satisfaction with their lives and, consequently, worse SRH. Studies

have shown that EAs with depression or dementia reveal worse SRH

compared to those who do not present any of these disorders9.

The

evaluation of SRH in EAs with depression, dementia, or delirium may be

complex. Cognitive impairment, per se, acts as an independent

predictor for mortality47.

Regarding

the relationship between the cognitive state and SRH, some authors

consider that cognitive alteration may make the SRH report unreliable,

particularly in patients with dementia48.

Others, on the contrary, consider that SRH is not altered. Walker et al.49

conducted a prospective population study with 8,697 elderly adults

living in the community in ten Canadian provinces to evaluate if SRH

behaved as an independent predictor for survival and determine if the

cognitive function could modify such relationship. It was found that

SRH was a valid measurement and predictive of survival in elderly

adults with minimal, slight, and moderate cognitive impairment. This

shows the complexity of the cognitive process in said relationship and

given that SRH is a subjective measurement it may reflect the state of

health the same way other objective measurements do, like the presence

of co-morbidity or the assessment of the functional state, within a

broad range of cognitive functioning.

Functional variables.

It is suggested that many chronic diseases have direct effects on SRH,

independently of the presence of disability or functional limitation.

Lammi et al.50 concluded that in contrast to the Framingham

study, diseases by themselves are stronger predictors of disabilities

than unhealthy habits, and that EAs judge their quality of life and

their health, more from the point of view of the capacity to

independently perform or not their daily life activities.

Likewise,

there is awareness of the association between co-morbidity and

functional impairment in physical and instrumental Basic Daily

Activities. Indeed, and as was already mentioned throughout this text,

the functional state is an important factor in determining SRH, which

shows the complexity of the multiple interactions existing between the

different factors determining it51.

From

another vantage point, although functional impairment and the presence

of chronic disease are important factors for the formation of the

subjective concept of a bad SRH; in spite of this, EAs with chronic

disease may report a good SRH. Such is the case of the Ontario health

survey conducted in 1990, where it was found that 79% of those with

chronic disease and 50% of those with long-term disability reported

good or excellent SRH52. This suggests that in spite of the

presence of chronic disease or disability, many EAs can perceive their

state of health favorably.

WHAT ADVERSE HEALTH EVENTS CAN SRH PREDICT?

Self-Rated Health has

been associated with health events like disease, death,

hospitalization, and functional impairment among others; however, some

of the factors determining SRH have also been associated independently

to health events, which lead to inferring that SRH acts as an

intermediate variable.

The

capacity of SRH to foresee morbidity has been considered good. Some

studies have shown that perceived morbidity coincides by two thirds

with morbidity diagnosed by healthcare personnel32. The

variables with greater association with the self-report of poor SRH are

the presence of chronic disease like hypertension, diabetes, urinary

tract disease, renal failure, acute illness, and functional like being

disabled, suffering a mental or physical disability or limitation53.

Hence, the perception of health and the factors associated with such

may be used to assess the level of health of the population of elderly

adults and its determinants53.

Also,

during the last 20 years there has been an important increase in

studying SRH as a predictor of mortality. Most studies find a

significant association between SRH and mortality54. Others

have found that the predictive value decreases, even losing its

significance when the analysis is adjusted according to other factors,

like prior morbidity or functional capacity55. Differences

in adjustment variables are also mentioned in the perception due to

gender or idiosyncratic variations in the population studied16.

Among

the arguments postulated to explain the capacity of SRH to predict

mortality, we have found, in the first place, past and current

knowledge of the health experience implying that EAs make a comparison

of their own health with people of similar age and state of health, and

in the second place, the personal health practices influencing on the

health results56.

The

relationship among SRH, mortality, and gender, is controversial. In

some studies, a stronger association has been demonstrated in males

than in females and a loss of meaning has been observed in women when

adding other variables, like the objective state of health when

participating in the interview57. In contrast, other studies have found the opposite effect, with a stronger association in women58.

These differences among different studies may be explained by the fact

that SRH does not have a unique point of reference; individuals use

personal perceptions, information from their neighbors and friends, as

well as objective medical information to have an idea of their state of

health.

Also,

regarding the relationship among socio-demographic factors, SRH, and

mortality, it is considered that said information may differ according

to gender, the moment of the vital cycle, or the social context. For

these reasons, it is interesting to study the relationship between SRH

and mortality in different populations and with different social

contexts59. The results among these three aspects,

socio-demographic factors, SRH, and mortality, have been contradictory

because some researchers have found that poor SRH is associated to

increased risk of death, even after adjusting it according to a broad

spectrum of socio-demographic variables acting as potential confounders16.

Other studies have not found a clear relationship between SRH and

mortality after adjusting it according to demographic, socioeconomic,

and clinical variables or psychosocial factors9. Some

authors have suggested possible explanations for these contradictions,

which include differences in the methods and ways of making the

questions and different types of response forms. There is also

reference to differences in the variables used for adjustment,

differences in perception due to gender or variations in the

idiosyncrasy of the population studied16.

It is

worth pointing out that studies in which the relationship between SRH

and mortality has been researched, the question has been dichotomized

in the following manner: good with options good and excellent and poor,

which includes regular, poor, and very poor. Furthermore, by including

multivariate logistic regression models, it was possible to evaluate

the association between SRH and mortality by adjusting for different

variables like chronic disease, habits (smoking, alcohol),

functionality, socioeconomic level, and others. When introducing these

analysis models, from decreased relative risk to a slight increase in

the association have been found. For example, a study carried out with

elderly Finish men during a 6-year period revealed a decrease in the

association of relative risk between mortality and poor SRH, which

decreased from 3.76 to 2.12 when the analysis was adjusted for eight

risk factors (body mass index, smoking, HDL cholesterol, LDL

cholesterol, blood pressure, physical activity, alcohol consumption,

and income)60. When a further analysis was done for eight

chronic diseases, the association diminished to 1.69. There is a

quantitative-type interaction because the means of association of the

effect have the same direction. Additionally, although the last

relative risk is lower, it is statistically significant and represents

a 69% increase in mortality for individuals reporting poor SRH.

Regarding

the relationship among measurements of SRH repeated over time and its

capacity to predict adverse health events, mixed results may be found.

Leinonen et al.61 conducted a cohort study with elderly

Finish subjects and after a follow up of the subjective assessment of

the state of health, they stated that stability is more common than

change in this assessment and systematically reflects the health

conditions, the functional capacity, as well as physical and social

activities. For the authors, the high stability in self-perception

indicates that with increased age, the elderly subjects adapt to worse

health conditions. This adaptation plays an important role that is

reflected in the subjective evaluation. Thus, the evident deterioration

in the objective evaluations is not subjectively reflected and the

authors suggest that the adaptation strategies to this deterioration

are given by modifications of expectations, aspirations, and standards

or that they see it as part of the normal aging process and adjust

their standards of good health accordingly. Furthermore, age-related

impairment is usually a gradual process to which they adapt slowly,

without simultaneously modifying their SRH; that is, there is a

cognitive reorganization for new internal processes. The stability may

also indicate comparison with other individuals in worse conditions or

with greater disadvantages. The few fluctuations in self-perception are

given by big or abrupt changes in the state of health or in the

symptomatology of the diseases, which also cause changes in the

functional capacity61. Given that SRH depends upon multiple

factors and among these there are the socioeconomic variables, said

hypotheses should be proven in developing nations so they can be

accepted and in this sense avail of their usefulness in our environment38.

In

terms of the cognitive function and the relationship between SRH and

mortality, it is known that SRH may adequately predict mortality in EAs

with slight, minimal and moderate cognitive impairment. For severe

impairment, its capacity to predict is affected and factors like age

and functional impairment take on greater importance49.

Likewise,

SRH has been associated as a predictive variable for hospitalization,

development of falls, functional impairment in the physical and

instrumental Daily Basic Activities, a greater demand for healthcare

services and institutionalization in nursing homes, after being

adjusted for possible confounding factors like socio-demographic

variables16.

In

conclusion, the concept of SRH has been broadly used, given that it is

a reliable and easily obtained measurement of the general state of

health, because it permits integrating a subjective measurement as an

indicator. Self-Rated Health is determined by the physical function,

the presence of disease, the existence of disabilities and functional

limitations. It has been associated with adverse health events like

mortality, use of healthcare services and impairment of physical and

instrumental Daily Basic Activities, becoming an important variable to

assess the state of health in the elderly.

REFERENCES

1. Manton KG,Gu X, Lamb VL.

Change in chronic disability from 1982 to 2004/2005 as measured by

long-term changes in function and health in the U.S. elderly

population. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006; 103: 18374-79.

2. Ocampo JM, Londoño I. Ciclo vital individual: vejez. Rev Asoc Colomb Gerontol Geriatr. 2007; 21: 1072-84.

3. WHO. Constitución de la Organización Mundial de la Health- Geneva, 1945. Date available: 6 November 2009.

4. Ocampo JM. Estrés y

enfermedades del adulto mayor. En: Herrera JA (ed).

Psiconeuroinmunología para la práctica clínica.

Cali: Programa Editorial Universidad del Valle; 2009. p. 109-28.

5. Ocampo JM. Evaluación geriátrica multidimensional del anciano en cuidados paliativos. P & B 2005; 9: 45-58.

6. Meléndez JC. La autopercepción negativa y su desarrollo con la edad. Geriatrika. 1996; 12: 389-1996.

7. Griffiths P, Ullman R,

Harris R. Self-assessment of health and social care needs by older

people: a multi-method systematic review of practices, accuracy,

effectiveness and experience. London: NCCSDO, 2005. Date available: 18

December 2006. Available in: http://www.sdo.lshtm.ac.uk/sdo302002.html

8. Bjorner, JB, Kristensen

TS, Orth-Gomér K, Tibblin G, Sullivan M, Westerholm P. 1996.

Self-rated health: A useful concept in research, prevention and

clinical medicine. Stockholm: Swedish Council for Planning and

Coordination of Research.

9. Idler EL, Benyamini Y.

Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community

studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997; 38: 21-37.

10. Aspiazu GM, Cruz JA,

Villagrasa FJR, Abanades HJC, García MN, Valero FA. Factores

asociados a mal state of health percibido o mala calidad de vida en

personas mayores de 65 años. Rev Esp Health Publica. 2002; 76:

683-99.

11. Damian J, Ruigomez A,

Pastor V, Martín-Moreno JM. Determinants of self assessed health

among Spanish older people living at home. J Epidemiol Community

Health. 1999; 53: 412-6.

12. World Health

Organization. Statistics Netherlands. Health interview surveys: towards

international harmonization of methods and instruments. Vol. 58.

Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, WHO Regional Publications,

European; 1996.

13. Engel G. The need for a new medical model: a Challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977; 196: 129-36.

14. Borrell-Carrio F, Suchman

AL, Epstein R. The bio-psychosocial model 25 years later: principles,

practice and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004; 2: 576-82.

15. Von Bertalanffy LV. Teoría general de los sistemas. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica; 1998.

16. Lee Y. The predictive

value of self assessed general, physical, and mental health on

functional decline and mortality in older adults. J Epidemiol Community

Health. 2000; 54: 123-9.

17. Ubel PA. What should I

do, doc?: Some psychological benefits of physician recommendations.

Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162: 977-80.

18. Blazer DG. How do you

feel about...? Health outcomes in late life and self-perceptions of

health and well-being. Gerontologist. 2008; 48: 415-22.

19. Wong R, Peláez M,

Palloni A. Autoinforme de health general en adultos mayores de

América Latina y el Caribe: su utilidad como indicador. Rev

Panam Health Publica. 2005: 17: 323-32.28.

20. Gómez JF, Curcio

CL, Matijasevic F. Autopercepción de health, presencia de

enfermedades y discapacidades en ancianos de Manizales. Rev Asoc Colomb

Gerontol Geriatr. 2004; 18: 706-15.

21. Parra DC, Gómez

LF, Sarmiento OL, Buchner D, Brownson R, Schimd T, et al., Perceived

and objective neighborhood environment attributes and health related

quality of life among the elderly in Bogotá, Colombia. Soc Sci

Med. 2010; 70: 1070-6.

22. Hambleton IR, Clarke K,

Broome HL, Fraser HS, Brathwaite F, Hennis AJ. Historical and current

predictors of self-reported health status among elderly persons in

Barbados. Rev Panam Health Publica. 2005; 17: 342-52.

23. Alves LC,

Rodrígues RN. Determinants of self-rated health among elderly

persons in São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Panam Health Pública.

2005; 17: 333-41.

24. Reyes-Ortiz CA,

Peláez M, Koenig HG, Mulligan T. Religiosity and self-rated

health among Latin American and Caribbean elders. Int J Psychiatry Med.

2007; 37: 425-43.

25. Department of Health.

2002. Guidance on the single assessment process for older people. HSC

2002/001; LAC (2002)1. London: Department of Health.

26. Bjorner JB, Tage SK,

Orth-Gomér K, Gösta T, Sullivan M, Westerholm P. Self-rated

health: a useful concept in research, prevention, and clinical

medicine. Stockholm: Ord & Form AB; 1996.33.

27.Ware JEJr, Sherbourne CD.

The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) (I). Conceptual

framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992; 30: 473-83.

28. McHorney CA, Ware JEJr,

Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item short-form health survey (SF-36): II.

Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical

and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993; 31: 247-63.

29. Lugo LH, García

HI, Gómez C. Confiabilidad del cuestionario de calidad de vida

en health SF-36 en Medellín, Colombia. Rev Fac Nac Health

Publica. 2006; 24: 37-50.

30. Eriksson I, Unden AL,

Elofsson S. Self-rated health. Comparisons between three different

measures. Results from a population study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001; 30:

326-33.

31. Jürges H, Avendano

M, Mackenbach JP. Are different measures of self-rated health

comparable? An assessment in five European countries. Eur J Epidemiol.

2008; 23: 773-81.

32. Seculi E, Fuste J,

Brugulat P, Junca S, Rue M, Guillen M. Percepción del state of

health en varones y mujeres en las últimas etapas de la vida.

Gac Sanit. 2001; 15: 217-23.

33. Hoeymans N, Feskens EJM,

Van den Bos GAM, Kromhout D. Measuring functional status: cross

sectional and longitudinal association between performance and

self-report (Zutphen Elderly Study 1990-1993). Clin Epidemiol. 1996;

49: 1103-10.

34. Liang J, Shaw BA, Krause

N, Bennett JM, Kobayashi E, Fukaya T, et al. How does self-assessed

health change with age? A study of older adults in Japan. J Gerontol B

Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005; 60: S224-32.

35. Idler EL. Age differences

in self-assessments of health: age changes, cohort differences, or

survivorship? J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1993; 548: S289-300.

36. Fries JF. Successful aging. An emerging paradigm of gerontology. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002; 18: 371-82.

37. Wong R. La

relación entre health y nivel sociodemográfico entre

adultos mayores: diferencias por género. En: Salgado de Snyder

V, Wong R, eds. Envejeciendo en la pobreza: género, health y

calidad de vida. México, DF: Instituto Nacional de Health

Pública; 2004. p. 97-122.

38. Palloni A, Pinto-Aguirre

G, Peláez M. Demographic and health conditions of ageing in

Latin America and the Caribbean. Int J Epidemiol. 2002; 31: 762-71.

39. Albala C, Lebrão

ML, León Díaz EM, Ham-Chande R, Hennis AJ, Palloni A, et

al. Encuesta Health, Bienestar y Envejecimiento (SABE):

metodología de la encuesta y perfil de la población

estudiada. Rev Panam Health Pública. 2005; 17: 307-22.

40. Wallace R, Herzog AR. Overview of the health measures in the Health and Retirement Study. J Hum Resour. 1995; 30: S84-107.

41. Baker M, Stabile M, Deri C. What do self-reported, objective, measures of health measure? J Hum Resour. 2004; 39: 1067-93.

42. Menéndez J,

Guevara A, Arcia N, León-Díaz EM, Marín C, Alfonso

JC. Enfermedades crónicas y limitación funcional en

adultos mayores: estudio comparativo en siete ciudades de

América Latina y el Caribe. Rev Panam Health Pública.

2005; 17: 353-61.

43. Leventhal H, Diefenbach

M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: using common sense to understand

treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn Ther Res.

1992; 16: 143-63.

44. Ocampo JM, Romero N, Saa

HA, Herrera JA, Reyes-Ortiz CA. Prevalencia de las prácticas

religiosas, disfunción familiar, soporte social y

síntomas depresivos en adultos mayores. Cali, Colombia 2001.

Colomb Med. 2006; 37 (Supl 1): 26-30.66.

45. Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003; 58: 249-65.

46. Lavretsky H, Kumar A.

Clinically significant non-major depression: old concepts, new

insights. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10(3):239 –55.

47. Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA,

Giles LC, Andrews GR. Demographic, health, cognitive, and sensory

variables as predictors of mortality in very old adults. Psychol Aging.

2001; 16: 3-11.

48. Hickey EM, Bourgeois MS.

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) in nursing home residents with

dementia: Stability and relationship among measures. Aphasiology. 2000;

14: 669-79.

49. Walker JD, Maxwell CJ,

Hogan DB, Ebly EM. Does self-rated health predict survival in older

persons with cognitive impairment? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004; 52: 1895-900.

50. Lammi UK, Kivela SL,

Nissinen A. Predictors of disability in elderly Finish men. A

longitudinal study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989; 42: 1215-25.

51. Idler EL, Kasl SV.

Self-ratings of health: do they also predict change in functional

ability? J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1995; 50B: S344-53.

52. Badley EM, Yoshida K,

Webster G. Disablement and chronic health problems in Ontario. Ontario

Health Survey 1990. Working Paper N° 5. Toronto: Ministry of

Health; 1993.

53. Lima-Costa MF, Firmo JO,

Uchoa E. The structure of self-rated health among older adults: the

Bambui health and ageing study (BHAS). Rev Saude Publica. 2004; 38:

827-34.

54. Heistaro S, Jousilahti P,

Lahelma E, Vartiainen E, Puska P. Self rated health and mortality: a

long term prospective study in eastern Finland. J Epidemiol Community

Health. 2001; 55: 227-32.

55. Murata C, Kondo T,

Tamakoshi K, Yatsuya H, Toyoshima H. Determinants of self-rated health:

Could health status explain the association between self-rated health

and mortality? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006; 43: 369-80.

56. Benyamini Y, Levanthal

EA, Levanthal H. Self-assessments of health: What do people know that

predicts their mortality? Res Aging. 1999; 21: 477-500.

57. Idler EL, Russell LB,

Davis D. Survival, functional limitations, and self-rated health in the

NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1992. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;

152: 874-83.

58. Leinonen R, Heikkinen E,

Jylhä M. Predictors of decline in self-assessments of health among

older people: a 5-year longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2001; 52:

1329-41.

59. Heistaro S, Laatikainen

T, Vartiainen E, Puska P, Uutela A, Pokusajeva S, et al., Self-reported

health in the Republic of North Karelia, Russia and in North Karelia,

Finland in 1992. Eur J Public Health. 2001; 11: 74-80.

60. Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE,

Everson SA, Cohen RD, Salonen R, Tuomilehto J, et al. Perceived health

status and morbidity and mortality: evidence from the Kuopio ischaemic

heart disease risk factor study. Int J Epidemiol. 1996; 25: 259-65.

61. Leinonen R, Heikkinen E,

Jylha M. Changes in health, functional performance and activity predict

changes in self-rated health: a 10-year follow-up study in older

people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002; 35: 79-92.

|